Reproduction

The

Photinus marginellus reproduce through means of

reproduction called nuptial gifts. Nuptial gifts are nutritional

contributions delivered from the male to the female during

sexual intercourse (Lewis et al., 2004). The nuptial gifts are

transferred through a spermatophore, which is a capsule of sperm

produced by the male accessory glands, and function to carry the

nuptial gift to the female during intercourse. The flash duration of the male

determines their spermatophore mass. The longer the flashes last,

the less spermatophore mass they have (Cratsley, 2004). As adults

most Photinus do not feed, therefore, reproduction is primarily

based on the resources received through the nuptial gift, and given

to the larva (Lewis et al., 2004). Nuptial gifts are of precise

economic importance within this insect group.

The male reproductive system for Photinus marginellus consists of

four pairs of accessory glands, which are tightly coiled and spiral

in shape. The most important of the four specific glands is the one

containing the spermatophore components, which house the nuptial

gifts (Lewis et al., 2004). The spermatophore, enclose the

pre-spermatophore, which are also spiral in shape, with two rows of

longitudinal pyramidal scales (Lewis et al., 2004). Aside from the

most prominent gland, the male has three additional glands that are

tubular and are each different in length. The long gland extends to

approximately 18-24 mm in length, while the medium gland greatly

declines in size into 5-7 mm long. The short, and last gland of the

three is approximately only 1 mm in length (Lewis et al., 2004).

During the early stages of intercourse, the four accessory glands of

the male secrete different fluids, which then all combine in the

male ejaculator duct with the sperm. The sperm have been pre-stored

in the seminal vesicles of the male organism. When the sperm has

come into contact with the fluid from the accessory glands, the

sperm become packaged into ring-shaped bundles, and are attached at

the end of the spermatophore (Lewis et al., 2004). This entire

spermatophore now has a gelatinous structure due to the fluid and

sperm combination. Within an hour of copulation, only part of the

spiral-coiled, gelatinous spermatophore has been transferred from

the Photinus marginellus male to the Photinus

marginellus female’s spermatheca, the female’s reproductive

storage for the encountered sperm. The remaining end of the

spermatophore enters the Photinus female’s reproductive tract in a

specialized structure called the spermatophore-digesting gland,

where the digesting gland functions to disintegrate the remainder of

the spermatophore within a few days (Lewis et al., 2004).

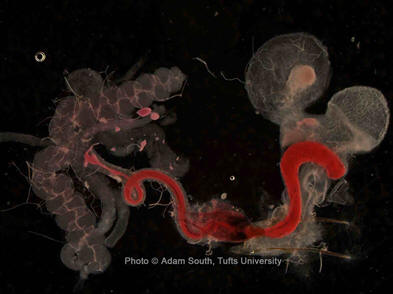

Figure 1. The Spiral spermatophore of Photinus marginellus,

inside the female reproductive tract. The spiral coils are visible,

and the sperm rings have been

released from the tip of the spermatophore into the female’s

spermatheca. This depicts the early stage of copulation (within

first hour) (Lewis et al., 2004).

The female Photinus marginellus then uses the spermatophore protein (nuptial gifts) to

develop their oocytes (a cell in an ovary, which undergoes mitosis

to form an ovum). The nuptial gifts, therefore, are important

supplements for support and nutrients to the larva in the female.

Nuptial gifts have evolved to be more than just a benefit to the

female, but a necessity as well. The nuptial gifts housed within the

spermatophore of the Photinus marginellus male provide the

Photinus marginellus females with energy reserves,

most importantly for non-feeding Photinus adults (Lewis et al.,

2004). In the non-feeding adults in particular, the energy reserves

diminish gradually in the larva, and need the nutrients in the

nuptial gifts from the Photinus male to supply the energy supplement. Also,

parasites could further reduce the resources needed for female

reproduction, which could be resupplied through the nuptial gifts as

well (Lewis et al., 2004).

Although production of a spermatophore is a beneficial necessity for

the Photinus females for reproduction, and the Photinus

males for sexual selection, it

is costly for the males to produce them. The spermatophore mass

decreases steadily, on average about 75%, between the first and

fourth sexual encounter with a female (Lewis et al., 2004). Also,

the cost of the spermatophore production may confine the male’s

mating success. Even if the Photinus males have access to a female on a

daily basis, the mating success declines, on average, during the

last half of the Photinus male's adult existence (Lewis et al., 2004). Due to

the limitations of the spermatophore production, this eventually

leads to the nuptial gift ability to decrease as the mating season

continues. The diminishing spermatophore mass, along with the

decreasing nuptial gift ability, could potentially lead to weakening

reproductive returns for the Photinus males (Lewis et al., 2004), meaning the

males would be unable to provide the spermatophores, and can no

longer copulate with a female.

It is clear that nuptial gifts influence Photinus marginellus in

very valuable ways. The nuptial gifts provide nutrients and energy

to the larva and to the Photinus female. The cost of the nuptial gifts and

production of spermatophore is very costly, and decreases with every

female the male encounters in sexual intercourse. The less

spermatophore the Photinus male can produce, the less nuptial gift

availability (Lewis et al., 2004), which, therefore, affects sexual

selection of the male (Cratsley, 2004). Early in the mating season,

when the male is the most readily able to generate spermatophores,

the sex ratios are male-biased, and can result in male-male

competition due to the Photinus marginellus females primarily preferring the

Photinus marginellus males that can provide the largest

amount of nuptial gifts. This is again expressed to the female based on the

intensity of the flashing

signals the male provides. However, later in the mating season,

females greatly outnumber the males as the spermatophore frequency

declines. The lower the intensity of flashes from the male’s abdomen, states

low spermatophore mass, which then causes the female to respond

elsewhere for greater production of the beneficial spermatophores

(Cratsley, 2004). To look at more information and pictures of

the difference between male and female Photinus marginellus

look on the website for the

Muesum

of Science, Boston; identifying genders. This page will show

you the difference between the male and female light organelles

and were they are placed. If you would like to gain more knowledge on

nuptial gifts in relation with sexual selection, visit the journal

article:

Nuptial Gifts and Sexual Selection in Photinus Fireflies.

The flashing light signals and how intense the Photinus marginellus male can radiate his bioluminescent glow are essential characteristics for the Photinus marginellus female to consider when choosing a male. These interactions play a giant role in sexual selection for reproduction between the Photinus marginellus male and Photinus marginellus female.