Habitat and Geography

By: Roslyn Walhovd

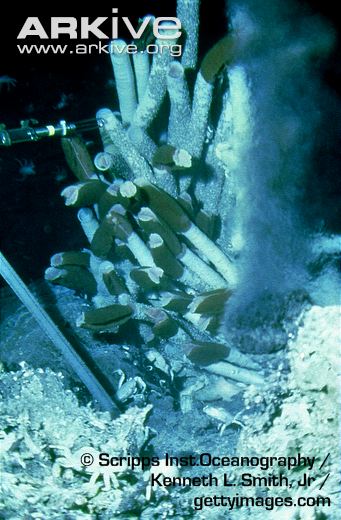

Riftia pachyptila, or more commonly known as the giant tubeworm, inhabits one of the best examples of a harsh environment: hydrothermal vents miles beneath the ocean surface, also commonly referred to as “Black Smokers” due to their appearance. These vents can be found in various locations across the Pacific and seeps at continental margins(Cone, 1991). Because of the extremes of the habitat only a few types of unique organisms inhabit them including microorganisms, crabs, fishes, and our own Riftia pachyptila. Other types of fauna like the common red algae can not inhabit the same areas as Riftia pachyptila. They have to be able to withstand as much as 300 ATM elevated pressure (Black, et all 1997), complete lack of light, temperatures rapidly changing from 4°C to 350° C and chemical toxicity (Black, et. all 1997)(Cone, 1991).

Hydrothermal vents are formed when seawater meets hot magma, this happens at

the divide of two tetonic plates, also know to be the site of crust

formation (Cone, 1991). This process heats the seawater up, dissolving large amounts of minerals. As the water

circulates it mixes with cool water forming mineral deposits and

vents. This forms a temperature and mineral gradient, which is

usable for chemoautotrophic organisms which can use these

dissolved chemicals to produce usable nutrients, much like other plants use

the sun. Chemoautotrophic organisms in a sense then is the key to life in

these harsh environments where other forms of usuable nutrients

are hard to come by (Cone, 1991)(Black, et. all 1997). These chemoautotrophic

organisms, bacteria, form symbiotic relationships with the

inhabitants of hydrothermal vents, much like we see in gut

bacteria of life above the surface. These chemoautotrophic

organisms live in the protection of the host and is

responsible for supplying the dissolved minerals form the

hydrogen sulfide rich environment (Feldback, 1981). The minerals are then

processed by the bacteria to provide enough food for itself and

its generous host.

Hydrothermal vents are formed when seawater meets hot magma, this happens at

the divide of two tetonic plates, also know to be the site of crust

formation (Cone, 1991). This process heats the seawater up, dissolving large amounts of minerals. As the water

circulates it mixes with cool water forming mineral deposits and

vents. This forms a temperature and mineral gradient, which is

usable for chemoautotrophic organisms which can use these

dissolved chemicals to produce usable nutrients, much like other plants use

the sun. Chemoautotrophic organisms in a sense then is the key to life in

these harsh environments where other forms of usuable nutrients

are hard to come by (Cone, 1991)(Black, et. all 1997). These chemoautotrophic

organisms, bacteria, form symbiotic relationships with the

inhabitants of hydrothermal vents, much like we see in gut

bacteria of life above the surface. These chemoautotrophic

organisms live in the protection of the host and is

responsible for supplying the dissolved minerals form the

hydrogen sulfide rich environment (Feldback, 1981). The minerals are then

processed by the bacteria to provide enough food for itself and

its generous host.

Another

obstacle of inhabiting these hydrothermal vents is the fact that

they are almost completely isolated from other marine

environments (MacDonald, et. all 1989). As you can image most marine life would perish

in such a difficult niche. These vents as we just learned are

not extremely common, they were only just discovered in 1977

(Cone, 1991)(Minic and Herve, 2004). Finding and colonizing new hydrothermal vent areas can

be very difficult. Riftia pachyptila has overcome this

difficulty somewhat in their type of reproduction. Female eggs

and male sperm are released into the environment and when

fertilized the larvae can life up to 40 days. This elongated

time period allows for Riftia pachyptila larvae to travel

distances of tens of hundreds kilometers to hopefully find and

cling to a new vent area (Feldbeck, 1981)(Black, et. all 1997). To this day Riftia pachyptila’s

life span is unknown. It is only noted that when the

hydrothermal vents cease, the days of this worm is numbered.

Dependent on the vent for the processes of life, the worms

shortly die out (Governar, et. all 2004).

Hydrothermal

vents are anything but easy to live in, it requires some extreme

specialization and even then this harsh environment is not a

cakewalk. Between huge amounts of pressure, dangerously high

temperature fluctuations, and extreme isolation, this place has

earned the right to the names “Black Smokers” and as Joseph Cone

said “Fire Under the Sea” (Feldbeck, 1981). Even our own amazing organism

Riftia pachyptila is at the will of these hydrothermal vents and

their processes.

For more information on organisms that live in light less habitates and their amazing specialization I would highly suggest reading about the bioluminescent astracod Photeros annecohenae. Several organisms that live with no light develop bioluminescense and it is a beautiful and intriguing adaptation.

Continue on to Form and Function