Adaptation

Structural and Physiological Adaptation

Teeth and Jaws

The saber-tooth tiger had very long canines

that were blade-like and curved slightly backwards (Turner 1997).

Data shows that the average rate of growth for the canines was about

seven millimeters per month and the length of the growth was about

18 months (Feranec 2003). While the canines were deadly weapons,

they were extremely fragile. The teeth must have been used

with care if damage was to be avoided. Paleontologists have

argued that conqueirng and killing the prey must have involved

techniques that differed from those utilized by living cats today.

Numerous ideas have been proposed to explain the elongated teeth,

but it is evident that the saber-tooth tiger could not simply sink

their teeth deep into the neck of an animal in the process of

wrestling it to the ground. The slightest movement from the

struggling prey would have threatened breakage in such an incident

(Turner 1997). Thus, while some hypotheses claim that Smilodon

fatalis used their canines to

sever the nerves and vessels in the neck region immediately during a

tackle, the accepted hypothesis states the saber-tooth tiger would

totally subdue their prey before simultaneously severing the blood

supply and strangling the windpipe. It would then

use its canines to rip the flesh off the victim (Prehistoric

Wildlife 2011).

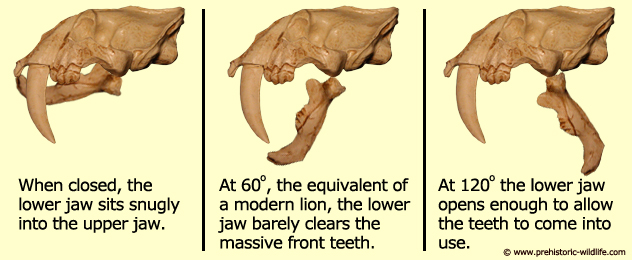

Furthermore, the saber-tooth tiger had weaker jaw muscles than other large cats with smaller teeth. The weaker muscles around the jaw joint allowed the prehistoric cat to open its mouth wider to 120 degrees (Feranec 2003). While this seems peculiar, it was an essential adaption if saber-tooth tigers were to get full use of their canines. Considering that the teeth were able to grow up to 28 centimeters long, the lower jaw would barely clear the bottom teeth if it could only open to 60 degrees (Prehistoric Wildlife 2011). Thus, it is believed that the saber-tooth tiger would have first used its massive forelimbs to subdue the prey before delivering the fatal strike of the canines.

For more information on the canines of Smilodon fatalis, visit

the

Science Direct Journal.

Limbs

Smilodon fatalis had shorter and thicker limbs than other

felines. Before delivering a fatal bite, the developed flexors

and extensors in the powerful forelimbs allowed S. fatalis to pull

down and hold onto the prey (Schmieder 2000). Because the

limbs were under repeated stress, the muscle constantly pulled on

the bone and the bone responded by getting stronger. Thus, the

limbs had powerful adductor muscles and thicker bone, which

helped with the prehistoric cat's stability and power when wrestling

with prey (Prehistoric Wildlife 2011). The shorter

limbs also provide evidence that they were not fleet-footed carnivores,

but rather ambush hunters that stalked their prey (Schmieder 2000).

Claws

All members of the Order Carnivora have claws, which grew

from the end of the third phalanges and were made of keratin (Turner

1997). The claws were generally sharp, curved, and sometimes impressively long

and functioned as weapons and grooming

tools. Like most cats, Smilodon fatalis claws had retractable claws.

Lack of Adaption to Environmental Changes: Extinction

Smilodon fatalis was adapted to the ice age

period of the Pleistocene epoch. They mainly fed on large herbivorous land mammals

and the open grasslands were their ideal hunting ground. Its

strong forelimbs were created for tackling the

large prey and the canines were used for severing the nerves and vessels of the neck

in the prey.

However, due to the weak jaw muscles and elongated canines of S. fatalis,

the prehistoric cats were not suitable for the changing climate of

the interglacial period, which was dominated by smaller animals.

Smilodon fatalis was adapted to the ice age

period of the Pleistocene epoch. They mainly fed on large herbivorous land mammals

and the open grasslands were their ideal hunting ground. Its

strong forelimbs were created for tackling the

large prey and the canines were used for severing the nerves and vessels of the neck

in the prey.

However, due to the weak jaw muscles and elongated canines of S. fatalis,

the prehistoric cats were not suitable for the changing climate of

the interglacial period, which was dominated by smaller animals.

Thus, concentrating on the last glacial and interglacial periods, the extinction of Smilodon fatalis can be explained. Due to the lack of adaptation of the large prey, there was a drastic decrease of the Smilodon's source of food, which in turn led to starvation. These large cats were unable to maneuver between the forests in the interglacial period; accordingly, S. fatalis was unable to catch their new agile forest prey.

At the same time, an increase in the temperature and precipitation influenced the ability to adapt to climate and terrestrial change. There is no solid evidence of Smilodon fatalis having fur; however, if thick hair were present on the cat, it would have protected them from the cold but led to hyperthermia in the heat (Prehistoric Wildlife 2011).

There is also the possibility that Smilodon fatalis had interactions with primitive humans during this era. Humans could have exclusively hunted S. fatalis into extinction or excessively hunted the prey of prehistoric cat leading to extinction.

To continue on the journey, visit

Life History next!

To return to the Smilodon fatalis homepage, click

here.