Interactions

Prey

Prey

Spotted eagle rays are an important component of the marine

food web. Aetobatus narinari are carnivorous benthic feeders

and have six primary prey categories: gastropods, bivalves,

crustaceans, echinoderms, polychaete, and other mollusks

(Schluessel et al. 2010). Approximately half of an eagle ray’s

diet is composed of gastropods, such as the endangered queen

conch (Strombus gigas), while the other half is mainly

made up of bivalves, including giant clams and calico clams (Macrocallista

maculata) (Randall 1967, Ajemian et at. 2012).

Occasionally, eagle rays will also feed on small fish, squid,

and cephalopods (Silliman and Gruber 1999).

Predation

In the marine food web,

A. narinari feed on

organisms on the benthic floor and in turn get preyed upon by larger

organisms. Due to their massive sizes, only the largest predators

pose a threat to this species. Sharks are their main predators.

Specific sharks that target A. narinari include the great

hammerhead (Sphyrna mokkarran), tiger (Galecerdo cuvier),

bull (Carcharhinus

leucas) and Carribbean reef sharks (Carcharhinus perezi)

(Silliman and Gruber 1999). Hammerhead sharks have been observed to

use a pin and pivot technique to capture and consume eagle rays

(Chapman and Gruber 2002). The shark pins the ray to the ocean floor

with its cephalofoil (flat portion of head seen in the photo to the

left) and then pivots its body

until the ray’s head is in its jaws.

In the marine food web,

A. narinari feed on

organisms on the benthic floor and in turn get preyed upon by larger

organisms. Due to their massive sizes, only the largest predators

pose a threat to this species. Sharks are their main predators.

Specific sharks that target A. narinari include the great

hammerhead (Sphyrna mokkarran), tiger (Galecerdo cuvier),

bull (Carcharhinus

leucas) and Carribbean reef sharks (Carcharhinus perezi)

(Silliman and Gruber 1999). Hammerhead sharks have been observed to

use a pin and pivot technique to capture and consume eagle rays

(Chapman and Gruber 2002). The shark pins the ray to the ocean floor

with its cephalofoil (flat portion of head seen in the photo to the

left) and then pivots its body

until the ray’s head is in its jaws.

Parasitic Interactions

A. narinari are

susceptible to a variety of parasites including trematodes, leeches,

and tapeworms. At least four species of Acanthobothrium are

known to have parasitic interactions with A. narinari. In

1995, a previously undescribed species of Acanthobothrium

was discovered in the spiral valve of a spotted eagle ray in the

Gulf of Nicoya. The parasite was named Acanthobothrium

nicoyaense and is a Cestode in the Phylum Platyhelminthes

(Brooks and McCorquodale 1995).

Another parasite that can

infect spotted eagle rays is a trematode called Clemacotyle

australis. In a study conducted by a zoo in the Netherlands,

infestations of C. australis have been shown to induce

stressful behavioral changes in spotted eagle rays (Janse and

Borgsteede 2003). A. narinari in captivity have been

observed leaping out of the water, swimming against strong currents,

and rubbing their bodies along the bottom of the aquarium in

response to the skin trematodes. These actions caused hemorrhages to

develop on their fins and altered their dorsal coloration due to

mucus buildup. If left untreated, the infection, along with the

immense energy expelled by the organism to purge itself, can result

in death. The addition of cleaner wrasse (Labriodes dimidiatus)

to A. narinari display tanks were shown to maintain the

infestation of C. australis at a level where they did not

negatively impact the health of the rays.

Aetobatus narinari & Homo sapiens

Some small fisheries, mainly in the

Southern Gulf of Mexico and Venezuela, specifically target spotted

eagle rays for their meat (Tagliafico et al. 2012). Meat obtained

from A. narinari is readily marketable in Venezuela and is the main

component of a popular dish. In other areas, the rays are often

unintentionally caught as bycatch from industrial fisheries, since

they dwell near the shore where fishing pressures are the greatest,

as mentioned in the habitat section.

A. narinari are classified by

the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List as

near threatened. Factors that have contributed to their status

include increased fishing pressures for numerous marine species,

overexploitation of these organisms and their primary food sources

(including bivalves and gastropods), and increased competition for

food and space due to a rise in the cownose ray (R. bonasus)

population (Cuevas-Zimbron et al. 2010).

Elasmobrachs,

including Aetobatus narinari, have stingers located on the

dorsal side of their tails. Since stingrays are generally peaceful

creatures, they use their stingers primarily as a form of defense

when provoked (Junior 2013). Their stingers are covered with a layer

of specialized epidermal cells that produce and secrete venom

(Pedroso 2007). Humans often accidentally come into contact

with these organisms while walking through waters near their habitat

or while attempting to release them from hooks and nets. Humans

inoculated with their venom can experience serious side effects,

including acute inflammation and pain, skin necrosis, and in some

extreme cases, death (Pedroso 2007).

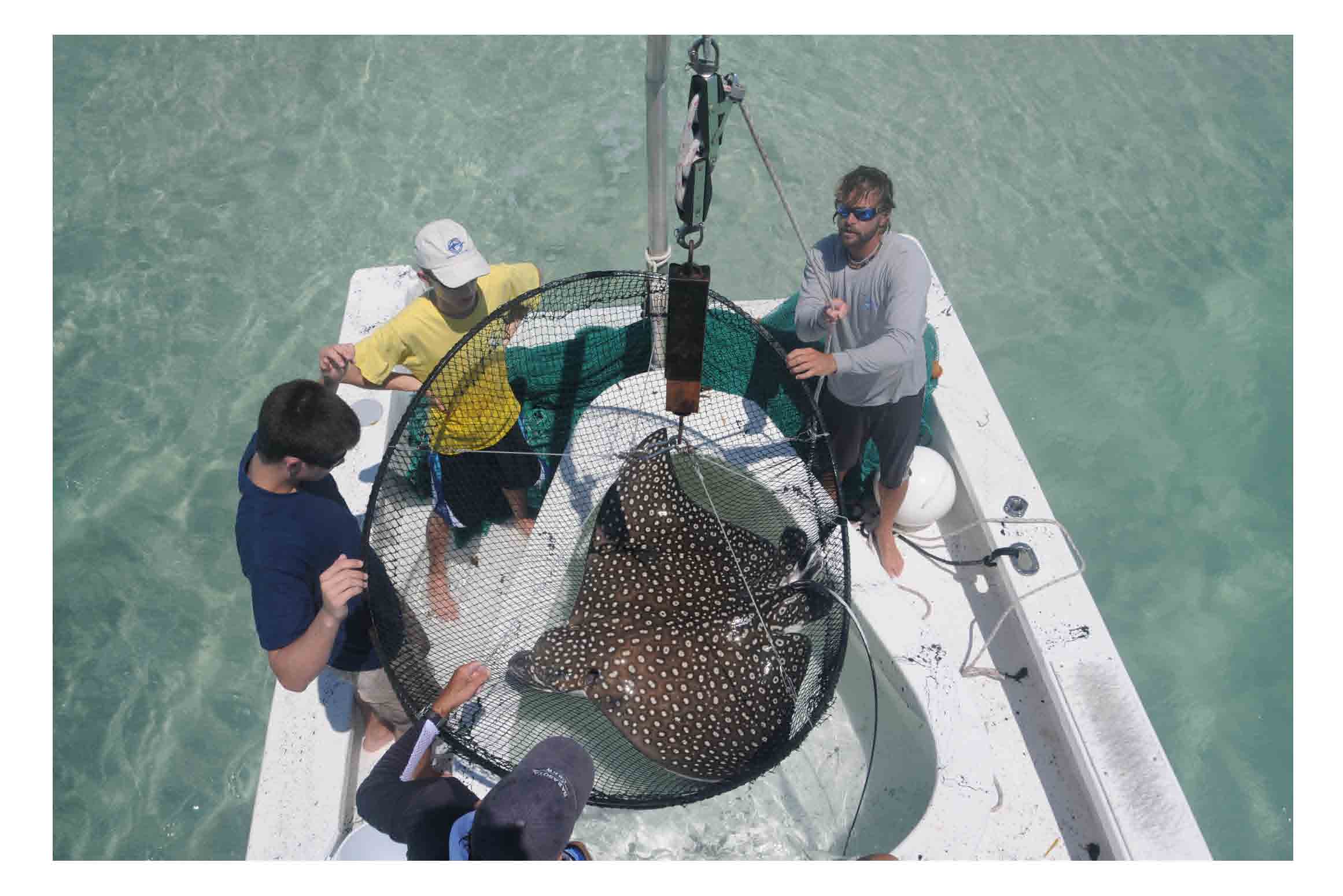

Spotted eagle

rays have also proven to be useful in research. Researchers can use

tissues found in their stinger to extract and analyze their DNA

(Janse et al. 2013). As the number of fishes worldwide starts to

deteriorate, breeding programs for animals in captivity become

important. DNA research and analysis can help maintain genetic

variability in captivity, and ensure successful future generations.

Lost stingers have the ability to easily grow back, so this method

of DNA acquisition is non-invasive and causes no lasting damage to

the organism. This DNA extraction method is also applicable to other

species of elasmobranchs. If you're interested in learning more

about the research being conducted on spotted eagle rays, check out this

video.

Continue on to learn about some really cool Facts, or return to the Home page.