Creating New Life in a Cycle

One distinction between Ascomycota from other fungi is the presence of a sexual cycle and an asexual cycle. Here, the focus is on these two crucial steps in forming new life for this species.

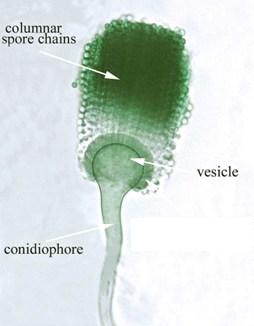

In the asexual cycle, haploid hyphae form foot cells which are diversions off of the hyphae. The tip of the foot cell swells, forming a conidophore vesicle. Through a series of mitotic budding events off of this vesicle, chains of haploid spores called conidia are formed. Once these spores are released, through a disruption in the environment, as mentioned in the adaptation section and the habitat section, the spores can grow to become haploid mycelia (Bennett 1992).

If the mycelia do not come into contact with other haploid mycelia, foot cells are grown to start further asexual reproduction. This happens in most conditions, but more spores are likely to be reproduced and become successful in the conditions described in the habitat section. Also, although it is unknown to this species, if the mycelia do come into contact with other haploid mycelia, sexual reproduction occurs.

In the sexual cycle, haploid hyphae connect in a process called plasmogamy. Once the plasma membranes fuse, they are said to be in a dikaryon stage (n+n). The two nuclei fuse in a process called karyogamy which occurs while the cell’s membrane shapes into an ascus, an elongated, oval shaped cell. This diploid ascus meiotically divides, forming four spores referred to as ascospores. Ascospores are released from the cup form of the fungi (the dikaryon ascocarp) into the air. If they survive, the ascospores grow into haploid mycelia, and the cycle continues (Freeman 2005).

Typical Life Cycle of Ascomycota

It is important to remember, asexual reproduction is favored in Aspergillus fumigatus during all conditions, especially those outlined in the habitat section. Sexual reproduction is unknown. This is why most human disease cultures contain conidia instead of an ascocarp.