Interesting Facts

Discovery in an Unusual Way

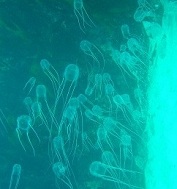

Wikimedia Commons: GondwanaGirl

Dr. Jack Barnes was a medical doctor in Australia

that saw many patients come to the hospital, suffering from a jellyfish sting,

and a number of them claimed to have never seen the culprit of their sickness.

This hellish sickness had already been given the name “Irukandji

Syndrome,” but the species responsible was not yet known. Dr. Barnes was

determined to discover the organism and deduced that he had to go in the water

because no one had ever found such a species on shore. So, he swam in unsafe

water where jellyfish stings were frequent. On December 10, 1961

he barely noticed a tiny, rather translucent jelly float in front of the glass

of his diver’s mask. He captured it, and a life guard, Don Ludbey, captured

another when he had noticed “an erratically swimming fish” that was being stung

by the organism. In order to conclude whether this was the culprit of

Irukandji Syndrome, Dr.

Barnes decided to perform a crazy experiment: He stung himself, his nine

year-old son, and life guard Don Ludbey. Within thirty minutes, they

were all experiencing extreme symptoms, proving that this little jellyfish was

indeed that cause of

Irukandji Syndrome. All three thankfully survived. This organism is now

named after its discoverer: Dr. Jack Barnes and Carukia barnesi.

(Nickson 2009)

Dr. Jack Barnes was a medical doctor in Australia

that saw many patients come to the hospital, suffering from a jellyfish sting,

and a number of them claimed to have never seen the culprit of their sickness.

This hellish sickness had already been given the name “Irukandji

Syndrome,” but the species responsible was not yet known. Dr. Barnes was

determined to discover the organism and deduced that he had to go in the water

because no one had ever found such a species on shore. So, he swam in unsafe

water where jellyfish stings were frequent. On December 10, 1961

he barely noticed a tiny, rather translucent jelly float in front of the glass

of his diver’s mask. He captured it, and a life guard, Don Ludbey, captured

another when he had noticed “an erratically swimming fish” that was being stung

by the organism. In order to conclude whether this was the culprit of

Irukandji Syndrome, Dr.

Barnes decided to perform a crazy experiment: He stung himself, his nine

year-old son, and life guard Don Ludbey. Within thirty minutes, they

were all experiencing extreme symptoms, proving that this little jellyfish was

indeed that cause of

Irukandji Syndrome. All three thankfully survived. This organism is now

named after its discoverer: Dr. Jack Barnes and Carukia barnesi.

(Nickson 2009)

Protection from Stings

Flickr: Matt Hobbs |

In 2009 Lisa-ann Gershwin and Karen

Dabinett published a research paper named “Comparison of Eight Types of

Protective Clothing against Irukandji Jellyfish Stings.” This study was

initiated by Surf Life Saving (SLS).

Gershwin and Dabinett explained

that these types of experiments need to be done because “less than five

percent of Queensland beach users wear any type of stinger protection,”

one-third of Irukandji stings occur in coral reef environments where tourist and researches

swim and dive often, and jellyfish stings are considered the “number one health

hazard in tropical Australian waters.” For the data collection, they

used two body suits meant for jellyfish sting protection, three types of panty

hose, and three types of sportswear suits.

Gershwin and Dabinett applied and

dragged tentacles across the materials and then observed many different factors:

In 2009 Lisa-ann Gershwin and Karen

Dabinett published a research paper named “Comparison of Eight Types of

Protective Clothing against Irukandji Jellyfish Stings.” This study was

initiated by Surf Life Saving (SLS).

Gershwin and Dabinett explained

that these types of experiments need to be done because “less than five

percent of Queensland beach users wear any type of stinger protection,”

one-third of Irukandji stings occur in coral reef environments where tourist and researches

swim and dive often, and jellyfish stings are considered the “number one health

hazard in tropical Australian waters.” For the data collection, they

used two body suits meant for jellyfish sting protection, three types of panty

hose, and three types of sportswear suits.

Gershwin and Dabinett applied and

dragged tentacles across the materials and then observed many different factors:

1. Penetrability- C. barnesi tentacles are only

one-fourth

millimeter in diameter, making it easy to get

through many looser knitted materials

2. Adherence- tentacles remaining stuck to

material can still

sting while taking off a suit

3. Crushing- if tentacles could be crushed through the fabric

4. Durability- how often will divers and swimmers need to

replace their protective suits

5. Heat retention- a major problem for

many divers and

swimmers who stay in the warm water,

under a hot sun, for long periods of time

6. Exposed skin- remember Irukandjis are tiny

and

can potentially sting ANY part of your body

7. Cost- always an issue of course, especially

if you’re

vacationing on a tight budget!

flickr: Holly VanDine

Gershwin and Dabinett concluded that there is no perfect protective suit. Often times, if one suit had small holes and thicker material, heat retention became an issue, or larger holes and thinner material left larger amounts of skin exposed, but were cheaper and decreased the possibility of heat retention. Gershwin, Dabinett, and SLS do not promote one particular type or brand of protective suit, but they do stress one key point that everyone should keep in mind when heading to beaches that have jellyfish (f.y.i., not just Australia has jellyfish!).

It is strongly recommended that when swimming in waters known to have jellyfish, some amount of the body, if not the entire body, should be covered with some form of protective clothing. Be smart and be safe!

Next stop: Irukandji Syndrome

UW-L

Last Updated: April, 26, 2013

Wikimedia Commons: Peter Southwood

Wikimedia

Commons: GondwanaGirl

Wikimedia Commons: Zaneta Nemcokova