Life History

Nutrition

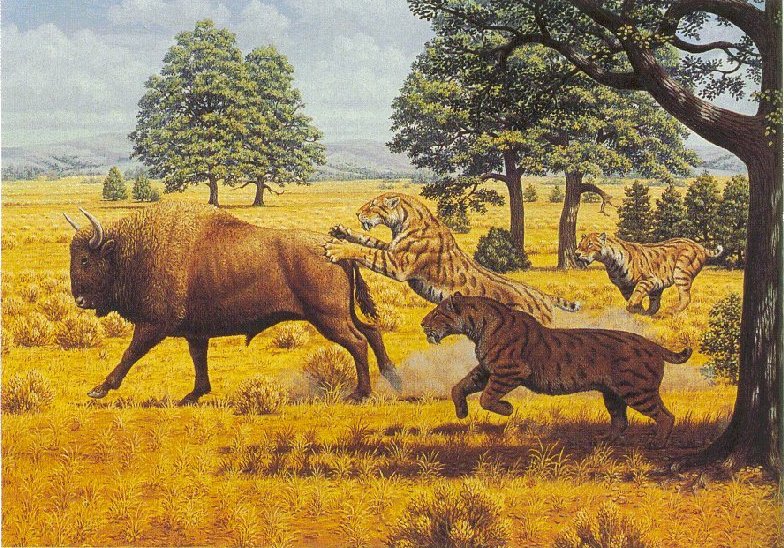

Smilodon fatalis was a carnivorous predator during

the Pleistocene epoch (Coltrain et al. 2004). Due to their robust physique, they were

believed to have preyed on large, slow moving animals (Coltrain et

al. 2004). Animals

that were within the hunting range of S. fatalis included

but were not limited to : the "yesterday's" camel, bison, pronghorns,

horses, ground sloths, mammoths and mastodons (Coltrain et al.

2004). Ruminant animals such

as the bison and camels were more likely to be hunted by S.

fatalis (Coltrain et al. 2004). To understand how these prey were captured, we have to

understand whether or not Smilodon were social. In this case,

S. fatalis probably was a social species inorder to compete

with other carnivores of the time (Carbone et al. 2009).

Smilodon fatalis was a carnivorous predator during

the Pleistocene epoch (Coltrain et al. 2004). Due to their robust physique, they were

believed to have preyed on large, slow moving animals (Coltrain et

al. 2004). Animals

that were within the hunting range of S. fatalis included

but were not limited to : the "yesterday's" camel, bison, pronghorns,

horses, ground sloths, mammoths and mastodons (Coltrain et al.

2004). Ruminant animals such

as the bison and camels were more likely to be hunted by S.

fatalis (Coltrain et al. 2004). To understand how these prey were captured, we have to

understand whether or not Smilodon were social. In this case,

S. fatalis probably was a social species inorder to compete

with other carnivores of the time (Carbone et al. 2009).

Intraspecific Interactions

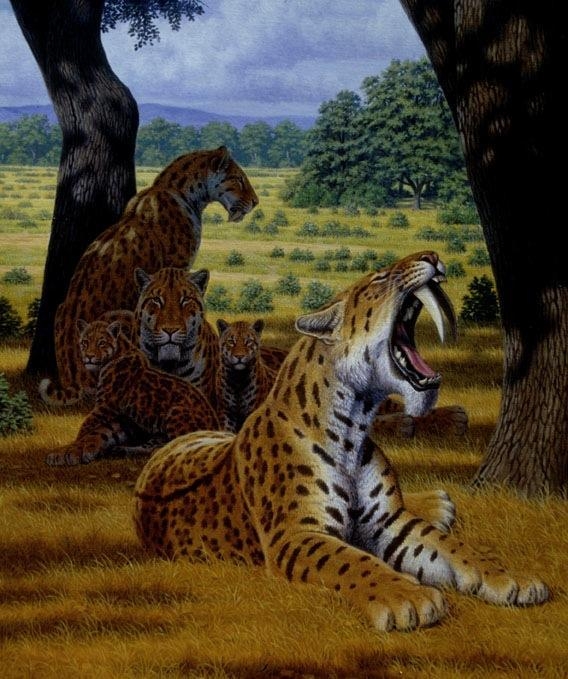

Smilodon fatalis was said to have been a social and solitary

species. Most arguments for either case are rigorous but there

is more

research supporting the idea that they were a social species.

According to the fossil records from Rancho La Brea, many Smilodon

bodies were found

together (Carbone et al. 2009). This suggests that Smilodon

hunted in groups as well as having a family structure. Nonetheless, it should be noted that they most likely were

sociable with one another. The social interaction between Smilodon are apparent

even in times of need.

Many

remains of the

saber-tooth

cat show signs of injuries to bones and

areas of muscle attachment that would take weeks to months to heal,

which would prevent a Smilodon from actively hunting. In solitary

creatures, these wounds would mean that the animal could not hunt and

would starve to death; however, most of the remains with injuries

show that these injuries healed or were in the process of healing

(Prehistoric Wildlife 2011).

Accordingly, the Smilodon must have gotten its food from somewhere

while it recovered. The most common accepted hypothesis is that these

prehistoric cats hunted in packs; thus, the food was shared among

the members of the group including the injured (Prehistoric Wildlife

2011).

The

La Brea tar pits also contained multiple sites where young Smilodon

were present in the presence of adult Smilodon and the prey

(Carbone et al. 2009). This

suggests that adolescent Smilodon accompanied the adults during

hunts to learn the strategies and instincts needed for survival

(Carbone et al. 2009).

Maternal care was also a plausible inference since the young could

not hunt until after their teeth erupted (Turner 1997). Scientists also inferred that after

teeth development, the mother would bring live prey for the young to

practice the instinct of biting (Turner 1997). Overall, the family structure was

thought to be quite similar to modern day cats.

To continue the journey, visit

Interactions next!

To return to the Smilodon fatalis homepage, click

here.