Habitat and Geography

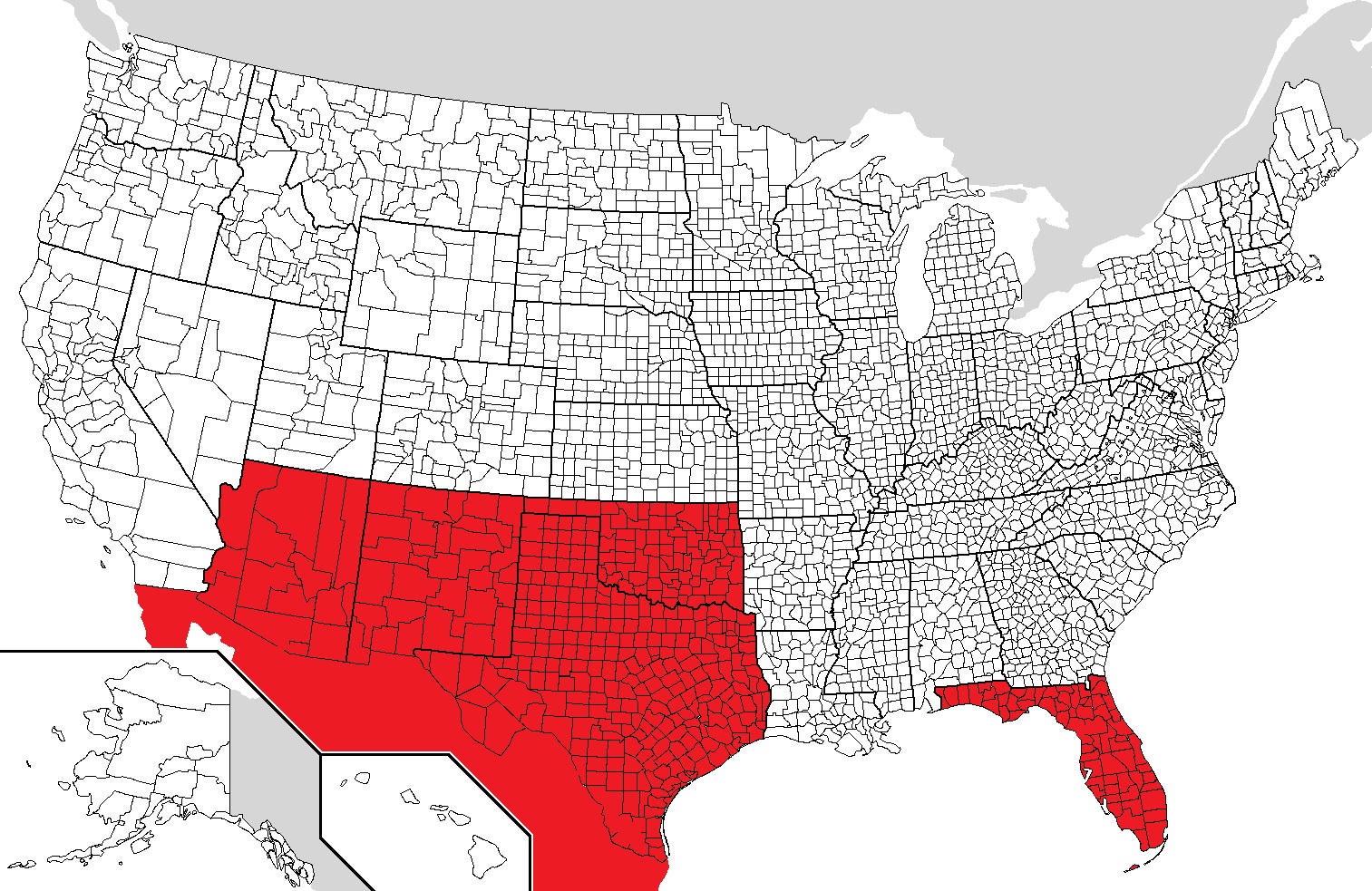

Whip scorpions are prevalent all around the world and are commonly

found in the tropics and subtropics, with most in tropical

rainforests (Kern and Mitchell 2011, Hembree 2013). However, Mastigoproctus giganteus whip

scorpions are burrowers which are typically found in dark,

seasonally humid areas like pine forests, grasslands, scrubs, and

barrier islands (Kern and Mitchell 2011). These areas

include dry areas of the southwest US and Mexico like Arizona,

Florida, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas (Schmidt et al. 1999, Kern and Mitchell 2011). This organism is found in specific

areas and is found in one type of habitat with almost no variation.

Interestingly, M. giganteus is in fact the only species of

whip scorpion which is found in the US.

Hembree 2013). However, Mastigoproctus giganteus whip

scorpions are burrowers which are typically found in dark,

seasonally humid areas like pine forests, grasslands, scrubs, and

barrier islands (Kern and Mitchell 2011). These areas

include dry areas of the southwest US and Mexico like Arizona,

Florida, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas (Schmidt et al. 1999, Kern and Mitchell 2011). This organism is found in specific

areas and is found in one type of habitat with almost no variation.

Interestingly, M. giganteus is in fact the only species of

whip scorpion which is found in the US.

These giant

whip scorpions use their massive pedipalps (claws/pincers) to

burrow themselves underneath many things like logs, rocks, and

rotting wood (Hembree 2013). Other places you can find these

creatures are in areas with loose soil, leaf litter, and the

scariest thought is in humid moist corners within buildings. M.

giganteus burrow themselves in well-drained soil during the

driest periods of the year and come up to the surface during May or

June. These creatures will continue to come to the surface during

the night until November while it is the rainy season (Kern

and Mitchell 2011).

Punzo (2006),

from the biology department at the University of Tampa conducted an

observational study where they discovered the shelter selections of

321 M. giganteus species during the daytime. Most (70.4%)

of the whip scorpions they found they discovered in rock crevices.

They also found that 4.4% of the sample size they found under plant

debris, and the remaining 25.2% were found inside of small pre-made

mammal holes. Due to being strictly nocturnal, none were found

outside of their burrows during the day. 66.7% of the shelter

samples found were also in the shade. The depth of M. giganteus

shelters varied from 6.4-39.7 cm and the width of the shelters they

found M. giganteus specimens in was between 0.7-2.9 cm.

Hembree

(2013), conducted an experimental study in which they took 18 whip

scorpions and put them into a controlled environment. Each

environment had a regulated temperature, controlled humidity and set

on a 12 hour light and dark schedule. The object of this experiment

was to get molds of the burrows for observation. Another goal was to

actually see the act of M. giganteus creating their

burrows. They left the whip scorpions in their enclosures for 14-16

days at a time and were randomly checked on to see any changes. What

Hembree observed while examining their burrows was, the M.

giganteus made two types of burrows. There were permanent

burrows which were built with greater care and were more complex.

The other kind of burrow, built with less attention to detail, was

the temporary burrow. The temporary burrows were classified as

burrows which were only in use for less than 72 hours. These

temporary burrows were quickly made and were generally a “J” shape.

The permanent burrows however were deeper, more complex, had bigger

tunnels, more turns and were constantly being modified. In the

beginning of the

experiment

the top of the soil in each tank was smooth. The experiment showed

the M. giganteus put the extra dirt and soil into piles

which built up to almost 10 cm of added soil around the entrance

hole(s). There were also impressions in the area around the opening

of the burrow from the whip scorpion. The impression marks and

mounds are all due to how it digs and the body structure of the whip

scorpion itself. The whip scorpions were fed crickets during the

experiment which showed the whip scorpion did not only use its

burrow for shelter, but also for hunting. During the

experiment the crickets put into the enclosures for food would enter

the burrow with the whip scorpion waiting to consume the cricket.

The whip scorpion doing this is able to consume its prey without

even leaving its burrow. To find out more about the eating habits

and the interactions with other species of M. giganteus

feel free to visit the Interactions

page.

experiment

the top of the soil in each tank was smooth. The experiment showed

the M. giganteus put the extra dirt and soil into piles

which built up to almost 10 cm of added soil around the entrance

hole(s). There were also impressions in the area around the opening

of the burrow from the whip scorpion. The impression marks and

mounds are all due to how it digs and the body structure of the whip

scorpion itself. The whip scorpions were fed crickets during the

experiment which showed the whip scorpion did not only use its

burrow for shelter, but also for hunting. During the

experiment the crickets put into the enclosures for food would enter

the burrow with the whip scorpion waiting to consume the cricket.

The whip scorpion doing this is able to consume its prey without

even leaving its burrow. To find out more about the eating habits

and the interactions with other species of M. giganteus

feel free to visit the Interactions

page.

Continue to Form and Function

Return to Home

See References