Habitat:

The Banded Mystery Snail is typically present in stationary or

slow-moving freshwater bodies because these are nutrient rich

environments. Viviparus georgianus prefers mud, sand, and

detritus-littered substrates along the edge or towards the bottom of

water systems, depending on the season. From spring to fall, the

Banded Mystery Snail spends most of its time towards the shore for

breeding purposes, and from fall to winter, it moves out to the

deeper benthic zones to prevent freezing and to find food. (Kipp and

Benson, 2011)

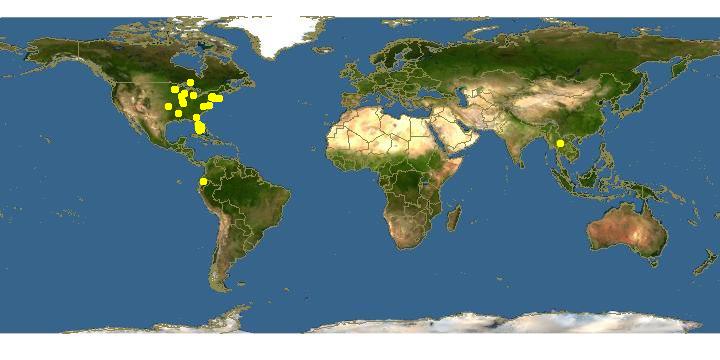

Viviparus

georgianus inhabits the Southeastern United States along with the

Mississippi and St. Lawrence River systems (Dillon, 2006). However,

it is native to Florida and Georgia and has invaded the Northeastern

states (Kipp and Benson, 2009). The Banded Mystery Snail, along with

other invasive gastropods, is being linked to ecosystem disruption

in nonnative habitats. Large numbers of water fowl deaths in the

Upper Midwest are occurring due to infections by trematode worms.

Viviparus georgianus is being linked to the infection because it is

believed to be an intermediate host to this parasitic worm. (Dillon,

2006)

Despite this

traumatic environmental impact, Viviparus georgianus fulfills an

important ecological niche. The Banded Mystery Snail has a large

variety of feeding methods. It is a grazer and filter-feeder that

consumes filamentous algae, diatoms, and suspended organic material

(Jokinen et. al, 1982) It will occasionally eat fish eggs and

decaying matter (Jokinen et. al, 1982). During the spring and

summer, it finds protection under macrophytes, which are water

plants that can be either floating or submerged (Kipp and Benson,

2010). Other organisms that coexist with this snail include mussels

and clams that filter-feed and compete for suspended organic material (Martin Kohl).

Viviparus georgianus provides food for organisms such as turtles,

fish, birds, and crayfish (Jokinen et. al, 1982). In addition, it is

a host for parasitic organisms such as annelid worms, protozoans,

and trematode larvae (Kipp and Benson, 2011).