Interesting Facts

There is still much to learn about the

Eudyptes schlegeli, but from what we do know, it is clear that the

Royal Penguin is a very interesting and unique species. The

bright yellow feathers atop of their heads captivate the

attention and bring smiles to the faces of most people who lay

eyes on them. This is just one of the many fascinating

characteristics that this species exhibits. These bright

feathers are not solely unique to

Eudyptes schlegeli.

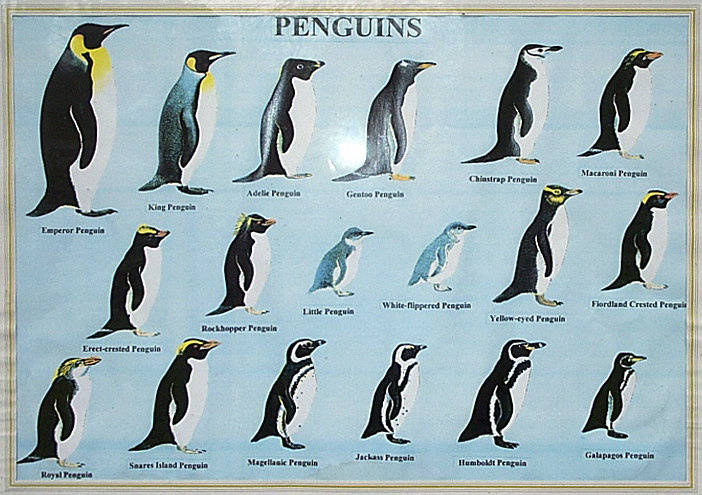

Royal Penguins belong to a group of several species of penguins

which share this characteristic (see

classification page). This group of penguins is

referred to as the crested penguin and makes up the genus

Eudypyes.

Also included in this

genus are the Erect-Crested Penguin

(Eudyptes

sclateri),

Macaroni Penguin (Eudyptes

chrysolophus), Snares Penguin (Eudyptes

robustus), Fiordland Penguin (Eudyptes

pachyrhynchus), as well as the Rockhopper Penguin (Eudyptes

chrysocome). Royal Penguins, along with Macaroni Penguins,

are the largest species of the crested penguin genus;

Eudypyes. In fact

until recently, the Royal Penguin was thought to be a subspecies

of the Macaroni Penguin. Royal Penguins have even been known to

interbreed with Macaroni penguins (Murphy, 2012.) (see

reproduction). This is happens on very rare occasions.

Other species of penguins have been known to infrequently

interbreed. There are two notable differences between

Eudyptes schlegeli and

Eudyptes chrysolophus. One is that the Royal Penguin has a

white face and chin, while the Macaroni Penguin has a black face

and chin. The other difference between these fairly similar

species is that the Royal Penguin is known to only breed at one

location, Macquarie Island. The Royal Penguin is the only

species known to inhabit this island, and it is not known as to

why they are the only species to inhabit this island. Macquarie

Island is an island that lies in the southwestern Pacific Ocean,

about halfway between New Zealand and the frigid continent of

Antarctica.

Royal Penguins, like other species of penguins, are

a colonial species. This means that instead of living solely in

monogamous pairs, Royal Penguins exist in colonies which generally stick

together. There has been an interesting finding pertaining to the

different colonies inhabiting this island. The diet of the penguins

seems to differ from colony to colony. This is especially particular

when contrasting the diet of colonies on the east coast of the island to

the colonies

together. There has been an interesting finding pertaining to the

different colonies inhabiting this island. The diet of the penguins

seems to differ from colony to colony. This is especially particular

when contrasting the diet of colonies on the east coast of the island to

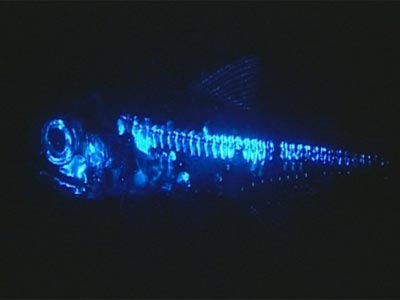

the colonies inhabiting the west coast. Overall though, half of the

Royal Penguin’s diet consists of small deep sea fish, namely lantern

fish from the family Myctophidae. About a quarter of the diet consists

of krill and other crustaceans from the family Euphausiidae. The other

quarter consists of namely squid and other various crustaceans (Royal

penguins. 2010, August 12).

inhabiting the west coast. Overall though, half of the

Royal Penguin’s diet consists of small deep sea fish, namely lantern

fish from the family Myctophidae. About a quarter of the diet consists

of krill and other crustaceans from the family Euphausiidae. The other

quarter consists of namely squid and other various crustaceans (Royal

penguins. 2010, August 12).

The largest colony of Royal Penguins is routinely found at Hurd Point during breeding season. Hurd Point is located at the southern point of Macquarie Island (see habitat page). This colony is estimated to be made up of around 1 million Royal Penguins, which is about half of the estimated global population of roughly 1,600,000 individuals (Ellenbroek, B. 2013.)

The

discovery of this species dates back to the 1800’s and is credited to

the famous zoologist Hermann Schlegel, which is how the Royal Penguin

acquired the scientific name

Eudyptes schlegeli. The Royal Penguin, like many other species of

penguins, is a monogamous species. Before mating, male Royal Penguins

perform a vertical head swinging motion, as well as a mating call (Waas

et al. 2000).

Eudyptes schlegeli is listed as a vulnerable species on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, which means that the species is in danger of becoming threatened, which is the stage before endangerment and extinction (Royal Penguins, Eudyptes schlegeli , MarineBio.org). They are listed as a vulnerable species largely because the population had been seriously affected by human overhunting in the past. Historically, humans hunted the Royal Penguins in order to harvest the oil that coats their feathers. Today we have found other means of obtaining similar oils, so the Royal Penguins are no longer hunted. Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Services have implemented regulations and restrictions which, in turn will only benefit the Royal Penguin’s population and habitat (Koehn, A. 2001.)

Since humans no longer hunt

Eudyptes schlegeli, their main predator consists of large seals.

Leopard Seals (Hydrurga leptonyx)

in particular regularly hunt

these penguins. The Leopard Seals hunt the penguins by biting the webbed

feet and thrashing and pounding them against the surface of the water.

Other predatory animals that prey on the Royal Penguin include orcas and

sea birds such as skuas, gulls and petrels (Ellenbroek, B. 2013.)