When a Mommy Shrimp and a Daddy Shrimp Love Each Other Very

Much...

Reproduction

We have all heard the story from our

parents, or teasing siblings, but this story somewhat holds true

for Pistol Shrimp. Most shrimp in the Alpheus genus

exhibit social monogamy and form a mated pair! (Masterson

2008). Mated shrimp will forage together, burrow together, and

have even been observed behaving slightly different toward each

other than to all the other shrimp (Srour 2012). Now that’s

true love!

A main factor that keeps this relationship together is mate

guarding by the male. Mate guarding is a defensive behavior by

the male to prevent other males from coupling with the female.

This decreases sperm competition while increasing reproductive

success between the mated pair (Stockley 1997). This is an

advantage to the pair due to the short time period the female

can become fertilized. This is where the process of molting

(see below for more detail)

becomes a very important part of reproduction. Female Pistol

Shrimp are only able to receive sperm from the male Pistol

Shrimp a few hours right after molting. Therefore having a

constant mated pair increases the chance of reproductive success

(Masterson 2008).

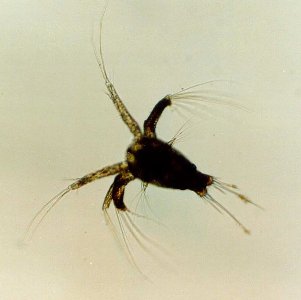

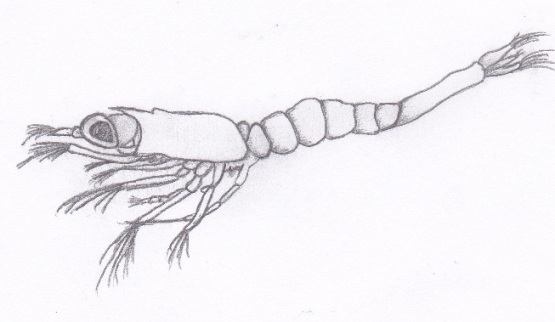

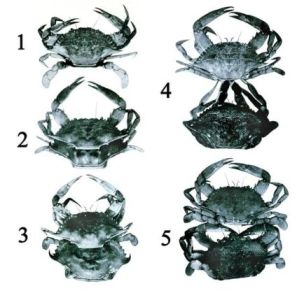

Shortly after mating, eggs are produced (Dobson 2011). The female invests 7% of her body weight in egg production (Pavanelli, et. al. 2010). These eggs are housed on the pleopods, or swimming legs of the female (Spence and Knowlton 2008). Once the eggs are laid, it takes about a month for them to hatch (Masterson 2008). When these shrimp first hatch, they are called nauplius larvae, which is the first of the larval stages. This stage has mandibles, two pair of antennae, eyes, and a body (Dobson 2011). This larvae feeds on yolk reserves until it becomes a zoea. The zoea is the next larval stage, which is noted by the growth of eye stalks and more appendages. This stage eats mostly algae and zooplankton (Spence and Knowlton 2008). The zoea then grows into the postlarvae stage, where they start to look like the adult form, but smaller (Dobson 2011). It takes about two to three weeks for the larvae to develop to this point (Spence and Knowlton 2008). The growth of the large claw comes some time later (Masterson 2008). Once the shrimp reaches full size through molting and can reproduce, the cycle starts again. As an adult, the Alpheid shrimp tend to have a mixed diet depending on the species. There are some that use sediment and sea grass as the main component of their meal (Palomar, et. al. 2004). They can be carnivores that use their claw to kill organisms like nematodes, small worms, crustaceans, amphipods, copepods and shrimp to eat. Others are detritus feeders, meaning they make dead organic material their dinner (Karplus 1999).

As mentioned in the Classification

page Alpheus randalli is an arthropod, so it has a

chitinous exoskeleton that does not grow with the organism.

Because of this, it must go through ecdysis, better known as

molting, to grow. Molting is the process of an organism

shedding its old exoskeleton when it outgrows it to make room

for the new, larger exoskeleton. During and shortly after

molting, the shrimps usually remain in their burrows for added

protection until their new exoskeleton hardens. They use this

for added protection because they are unable to snap their claw

because of their soft exoskeleton and within the first day, the

shrimp cannot even open their chelae (Zeng and Jaafar 2012).

So what is so great about this claw and how do they create that snapping noise? Continue on to the Spooky Story page to find out about the claw and why it's so frightening.