Interactions

Because Solenopsis invicta is an

“invasive” species, it is implied that this is a harmful or

disruptive species. Indeed, these ants do have quite a large

negative impact on many other organisms. Although conducting

experiments to discover long term impacts on

different species on a large scale is difficult, small scale

observational studies can be very informative (Allen et al.

2004).

Small animals are at high risk for being negatively affected

by S. invicta, especially ground nesting organisms

(Smithsonian Marine Station 2007). Reptiles are prime examples,

because the adults do not provide proper care to their young if

their nests have been infiltrated by RIFAs (Allen et al. 2004). Snake and amphibians are

also in this same situation, although much attention has been

focused on sea turtles. According to a study performed in

2009, Loggerhead sea turtle eggs are especially susceptible to

being breached by foraging ants (Diffie et al. 2010). RIFAs

will sting and eat hatchlings, which overall devastates sea

turtle populations (Allen et al. 20 04).

Birds, such as doves, terns, and northern bobwhites have also

been found in lower numbers in invaded areas, and small

mammals are also profoundly impacted. These mammals have far

lower species richness in infested areas than their

counterparts in unaffected regions (Allen et al. 2004).

04).

Birds, such as doves, terns, and northern bobwhites have also

been found in lower numbers in invaded areas, and small

mammals are also profoundly impacted. These mammals have far

lower species richness in infested areas than their

counterparts in unaffected regions (Allen et al. 2004).

Red Imported Fire Ants also affect native ant species. Areas

with small populations of RIFAs and higher diversity of other

ant species show that competition may occur, although studies

also show native ant species and RIFAs can coexist (Cumberland

and Kirkman 2012). Human involvement in the eradication of

S. invicta has actually caused greater strife between

native and invasive species than actually occurs in nature. Air

sprayed with pesticides in the southeast United States was an

attempt to kill off the invasive RIFAs, but also killed off

native ants. The harmful pesticides actually caused more

devastating distresses (Encyclopedia of Life 2013). The RIFAs, being

more efficient at reproduction and colonization, recovered

faster than native species, therefore becoming more dominant and

worsening the problem (Gordon 2010). The native ants did

recover, but human contribution did not help the situation which is still a struggle to this day.

Humans have been working towards getting rid of the pesky Red

Imported Fire Ants across the globe, especially in the United States since they were

accidentally introduced from South America about a hundred years

ago (Encyclopedia of Life 2013). However, most attempts have been

futile. RIFAs have been responsible for substantial crop

damage. The Department of Agriculture has estimated that these

ants have cost about 6.5 billion dollars between damages and

control of population (Smithsonian Marine Station 2007). To

learn more about the economic impact of S. invicta,

please visit

http://entoplp.okstate.edu/ddd/insects/rifa.htm.

Besides

crop damage, RIFAs are simply an annoy ance. The venom of

Solenopsis invicta unique in that fact that is contains

95% alkaloid and only a small amount of protein, while most

other ant and wasp venoms contain little to no alkaloid.

This toxic special property of the venom causes a very

unpleasant reaction in victims (Taber 2000). Even slight contact of skin

with a nest will lead to a plethora of stings, which are very

painful (Gordon 2010). The pustules that form are necrotic,

causing cells to die, due to the poisonous venom which the ant

releases when it stings (Klotz et al. 2008).

ance. The venom of

Solenopsis invicta unique in that fact that is contains

95% alkaloid and only a small amount of protein, while most

other ant and wasp venoms contain little to no alkaloid.

This toxic special property of the venom causes a very

unpleasant reaction in victims (Taber 2000). Even slight contact of skin

with a nest will lead to a plethora of stings, which are very

painful (Gordon 2010). The pustules that form are necrotic,

causing cells to die, due to the poisonous venom which the ant

releases when it stings (Klotz et al. 2008).

However, Red Imported Fire Ants aren't solely pests. Some

colonies actually have a mutualistic association with plants.

The plant provides space for a nest to form as well as

nutritious nectar, while the ants protect the plant from

herbivores (Gordon 2010). As mentioned in The Southwestern

Naturalist, specifically there is facultative mutualism between

RIFAs and a particular type of legume, Senna occidentalis (Fleet

and Young 2000). Large colony size and large individual ants

ma y provide an even better form of protection for these legumes

(Fleet and Young 2000).

y provide an even better form of protection for these legumes

(Fleet and Young 2000).

Within colonies, RIFAs interact and communicate via

chemicals known as pheromones (Taber 2000). Ants also

use “recruitment” pheromones as a trail for other ants to follow

in order to find a food source (Taber 2000). RIFAs are

foragers and predators, feasting upon anything from seeds, to

termites and miniscule invertebrates, and scavenging on dead

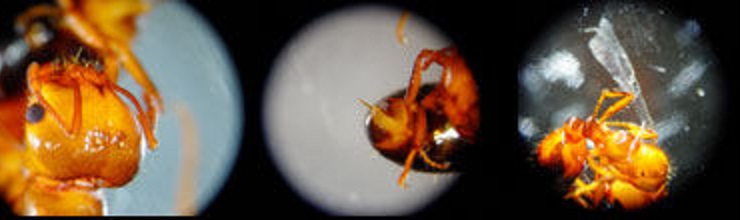

organisms (Asano and Cassill 2012). The image to the right

clearly depicts how aggressive RIFAs can be when hunting for

food. To view even more photographs of the fascinating

S. invicta , click here to

visit the gallery.

Click here to return to the home page.