Reproduction

Solenopsis invicta, more

commonly known as the Red Imported Fire Ant or RIFA, is one of the most successful invasive

species on the planet. Therefore, they must be very quick and

efficient at reproduction (Taber 2000). The mating of

these ants is a unique

process, and usually occurs between spring and fall. However,

they have been known to mate in the winter in places where climates

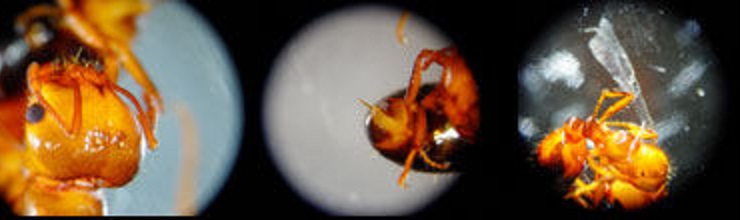

are warm (Taber 2000). Winged males and winged females, called

alates, engage in a mating ritual while in flight (Smithsonian

Marine Station 2007). Amazingly, some of these mating individuals

have been captured at heights approaching 1000 feet in the air

(Taber 2000). The male dies shortly after the mating process

concludes. Females remove their wings after the mating ritual as

well, so they can en compass their reproductive roles more

entirely (Klotz et al. 2008). The female, or queen, then finds

a suitable location to begin a colony (Smithsonian Marine

Station 2007). She will then dig chambers into the ground, where she

will lay her initial batch of eggs (Entomology and Plant

Pathology 2013).

compass their reproductive roles more

entirely (Klotz et al. 2008). The female, or queen, then finds

a suitable location to begin a colony (Smithsonian Marine

Station 2007). She will then dig chambers into the ground, where she

will lay her initial batch of eggs (Entomology and Plant

Pathology 2013).

Once eggs are laid by the queen, she covers them with

antibiotic venom to protect the offspring, which may also be

used as a signal for workers to carry them away to a different

part of the nest. However, the first batch

of eggs is raised in a way that differs from the future

generations to come. These eggs are nourished by the queen

herself via nutritious trophic eggs, oil she has regurgitated, or her own

saliva (Smithsonian Marine Station 2007). These first eggs are

hatched, but are smaller than future generations due to the fact

that the queen has to feed them herself. These first female

workers then develop and take charge of feeding future offspring

of the queen (Smithsonian Marine Station 2007).

Ants develop in stages, starting as eggs and further

developing to larvae, pupae, and finally adult form (Klotz et

al. 2008). A unique feature to S. invicta

colonies is that the queens can produce diploid males, unlike

many other ant species (Taber 2000). However, a feature of all

ants is that they are eusocial insects, which influences their

success. They exhibit cooperative

care of the young, labor division, and an overlapping of

generations in their colonies. A mature colony, which reaches

this point three years after initial copulation, may comprise of

anywhere between 100,000 and 500,000 workers, and hundreds of

alates (Entomology a nd Plant Pathology

2013). S. invicta

queens can live to be up to seven years old, which helps

attribute to how successful colonies are at reproduction (Taber

2000).

nd Plant Pathology

2013). S. invicta

queens can live to be up to seven years old, which helps

attribute to how successful colonies are at reproduction (Taber

2000).

A unique occurrence in the species S. invicta is

that it has evolved both social forms that are found in ant

colonies. One type of colony is the multi-queen polygene form,

which has many queens that are not territorial (Klotz et al.

2008). There can be thousands of queens in this form of colony,

some which are mated and some which are not. Polygene colonies

can grow to be so large that they can have numerous mounds per

colony (Taber 2000). This form of colony is thought to be more

successful in respects to density of population than the second

type, the monogyne colony. This other type of colony is singular

and territorial, with one queen. This form

of colony has subsequently low population densities (Klotz et

al. 2008). Infiltrations by monogyne nests are also less

numerous and calamitous than the polygene type (Allen et al.

2004). However, monogyne queens each lay far more eggs than their

polygene counterparts, and their workers are larger in size

(Taber 2000).

No matter what form of colony that S. invicta displays,

one thing is certain. The reproductive success of this invasive

species is very impressive, especially in the places all around

the globe to which they have spread besides their native lands

of South America. This copious invasive species has major

impacts and interactions with many different organisms. Click

here to learn more about the

interactions of S. invicta.

Click here to return to the home page.