Habitat

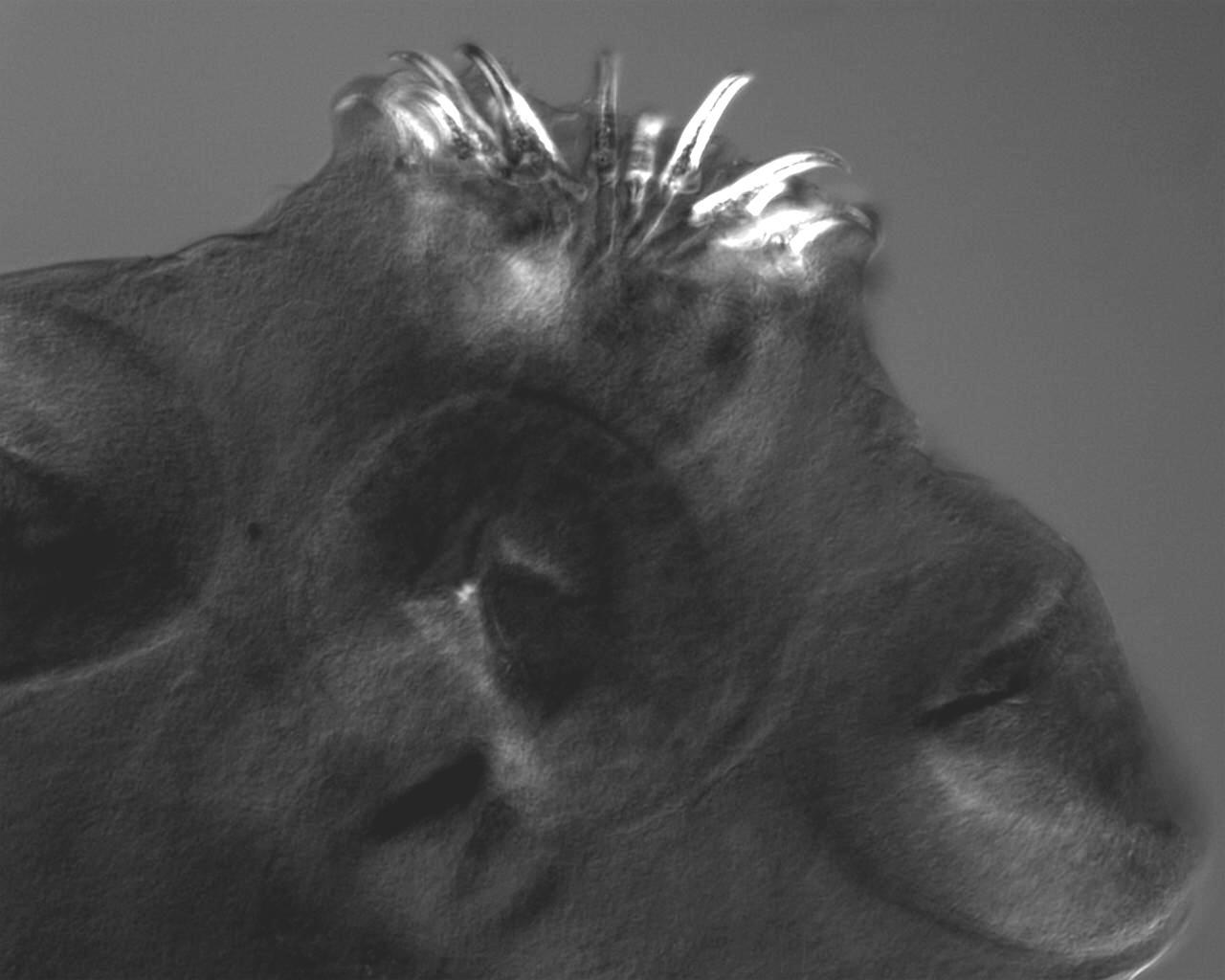

T. solium scolex

Intermediate Host: Pigs

T. solium use pigs an intermediate host, and live in a variety of pig tissues, most commonly skeletal muscle. They migrate via the blood stream to skeletal muscles and encyst. These cysts are known as cysticerci. The larval form will remain encysted in the muscle cell of the pig for years, until it is consumed by the definitive host; us.

Definitive Host: Humans

Humans are infected by T. solium by eating uncooked pork. The cysticercus will then develop into an adult tapeworm in the small intestine of the human. T. solium will attach to the human's intestinal wall via its scolex, and remain there to acquire nutrients and reproduce. If not treated it will remain in the small intestine for years

An Accidental Intermediate Host: US!!!!

While being the definitive host of a tapeworm is not something that seems particularly pleasant, it pales in comparison to being the intermediate host. Sometimes, through auto-infection, or contaminated food and water people become the intermediate host of T. solium. If this occurs, rather than the adult living in a person's digestive tract, the larval form will migrate to virtually any tissue in the human body and encyst. This can cause a number of health problems, and possibly death.

Cysticerci in skeletal muscle near the human pelvis

T. solium, and the multitude of health problems it can cause, are most prevalent in developing countries where pigs are raised. Many times the pigs graze in close proximity with humans, and these areas often exhibit poor sanitary conditions. Because of this, the pigs' food supply is contaminated with human feces, creating a perfect situation for T. solium to spread. This problem is exacerbated in some cultures where it is custom to eat raw or undercooked meat. Because of the fact that the intermediate host is a pig, it is rarely found in Muslim communities where pork consumption is forbidden. It is endemic in South America, Central America, India, southern Asia, Africa, parts of southern Europe, and parts of Mexico. It is also seen in areas of the world that experience large amounts of immigration.

Let's all put on our anthropologist

hats

Why might these countries have such high instances of T. solium infection? Some people in these areas farm pigs as a means of subsistence agriculture, and need to continue to do so to provide food for their families. Pig farming is also important for economic gain and social status in some developing countries.

Sometimes cultural rituals are the reason people are infected. For instance, the Sotho of South Africa trust faith healers to administer T. solium eggs to cure various ailments or to smite one's enemies. They also seem to understand that there is the possibility of death associated with this practice, but trust the healers to administer the procedure safely. There are also cultures in which it is custom to eat uncooked pork, despite the fact that they understand the inherent danger of parasite infection

Bottom Line:

In developing countries, raising pigs is an important means of income, and as a source of nutrition. Many cultures also have traditions and rituals which result in exposure to the potentially deadly parasite. Some cultures view ownership of livestock to be an important symbol of social standing. Others have traditions ranging from occasionally eating small amounts of uncooked meat to knowingly becoming infected. These are among the many significant cultural reasons why these regions continue to exhibit endemic levels of T. solium infection.

In these regions of the world, however, some hope may be coming in the form of pig vaccinations. In an attempt to break the lifecycle of T. solium, some researchers are testing the effectiveness of these drugs and finding great success. One study I read had results ranging from 98.6 to 99.9% infection free pigs. Further study is needed, and it is no guarantee that these measures will be available or become common practice in the endemic regions, but it is a good start