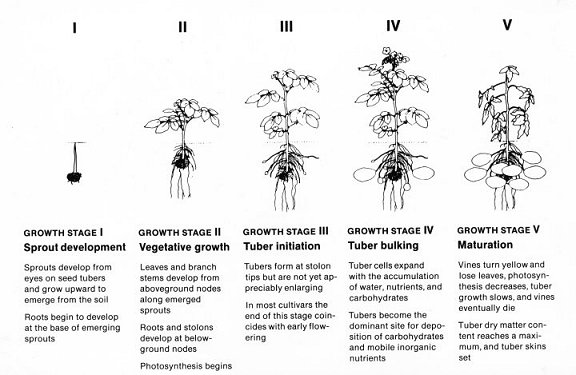

Growth Stages

The growth of a potato can be broken down into five stages.

The table above has been reproduced with permission from

Johnson, D. A., ed., 2008, Potato Health Management, 2nd ed., American Phytopathological Society,

St. Paul, MN.

Growth Stage I: Sprout Development

The first stage begins with sprouts developing from the eyes and ends at

emergence from the soil. The eyes

of a potato are the little black spots that appear on the skin of the potato.

The stems of the potato sprout from the eyes.

The seed piece, or seed tuber, is the only energy source for growth

during this stage.

Growth Stage II: Vegetative Growth

The second stage is the stage in which all vegetative parts of the plants

(leaves, branches, roots, and stolons) are formed. It begins at emergence and

lasts until tubers start to develop.

Growth stages I and II last from 30 to 70

days depending on planting date, soil temperature, climate, and other

environmental factors. Potatoes grown in

Wisconsin, for instance, don’t have a long growing season, so the first two

stages can’t take 70 days or the plants would never produce any tubers.

Growth Stage III: Tuber Set/Initiation

During the third stage of growth, tubers are forming at stolon tips, but are

not yet enlarging. If you were to dig up a potato plant, the tubers would be

about the size of a jelly bean and would look like a mini potato.

This stage lasts about two weeks. This occurs between early and late June depending on location, planting

date, climate, soil type, and variety. Tubers form when the plant produces more

carbohydrates than are required for vine growth. Varying weather and moisture

conditions cause uneven tuber set and growth. on location, planting

date, climate, soil type, and variety. Tubers form when the plant produces more

carbohydrates than are required for vine growth. Varying weather and moisture

conditions cause uneven tuber set and growth.

The number of tubers formed per plant is called the tuber set. The plant may

initially produce 20 to 30 small tubers, but only 5 to 15 tubers typically reach

maturity, 15 being an extremely high case. The growing plant absorbs some of the

tubers in the original set. The number of tubers that achieve maturity is

related to available moisture and nutrition. Optimum moisture and nutrient

levels early in the growing season are critical to the maintenance and

development of tubers.

Because water

levels are so important, farmers will irrigate their fields on a daily basis and

sometimes more if needed. This is

why you may see irrigation systems running at night, as well as during

the day.

Different farmers have different strategies about irrigating fields.

When a field is irrigated during the day, the potato plants are cooled

and the leaves are less susceptible to heat damage.

However, some of the water evaporates because it is so hot out, so the

farmer has to put more water on the field.

Irrigating at night makes sure most of the water is absorbed by the

plant, but it doesn’t cool off the plant during the day.

So many choices! the day.

Different farmers have different strategies about irrigating fields.

When a field is irrigated during the day, the potato plants are cooled

and the leaves are less susceptible to heat damage.

However, some of the water evaporates because it is so hot out, so the

farmer has to put more water on the field.

Irrigating at night makes sure most of the water is absorbed by the

plant, but it doesn’t cool off the plant during the day.

So many choices!

Growth Stage IV: Tuber Bulking

Tuber cells expand with the accumulation of water, nutrients and

carbohydrates. Tuber bulking is the growth stage of longest duration. Depending

on date of planting and other factors, bulking can last up to three months, but

it usually lasts about 45-60 days.

Growth Stage V: Maturation

Vines turn yellow and lose leaves, photosynthesis gradually decreases, tuber

growth rate slows and the vines die. This stage may not occur when growing a

long season variety like Russet Burbank (the potatoes you most commonly used for

baked potatoes) in a production area with a short growing season like Wisconsin.

In that case, the plant is killed using an herbicide s o the tuber can grow a

little bigger before harvest. The

fields are also killed to minimize the work the farm equipment has to do in the

field. o the tuber can grow a

little bigger before harvest. The

fields are also killed to minimize the work the farm equipment has to do in the

field.

Some other varieties like Goldrush and Norkota, however, will complete this

stage and there will be almost nothing left of the plant but decayed stems and

leaves when it is time to harvest the potatoes.

Red potatoes, on the other hand, are cut short of their maturation period

because consumers like eating the small red potatoes and farmers can’t sell

their red potatoes if they get too large.

Check out the Reproduction/Cloning

page to learn about how farmers clone the potatoes you eat!

|