The Most-Traveled Cane Toad

The Many Homes of the Cane Toad

The following questions are answered on this page. Either click on the following bookmarks, or just read down the page!

How or why is the cane toad outside of its native habitat?

What characterizes cane toad habitat?

What effect have humans had on toad habitat?

Where is the native habitat for the cane toad?

Where all does the cane toad now call home?

How

or why is the cane toad outside of its native habitat?

The migration of the cane

toad is a long story, and wh

How

or why is the cane toad outside of its native habitat?

The migration of the cane

toad is a long story, and wh ile the toad is very adaptive, it

could not have accomplished its feats without humans!

So, let us begin our story with why

humans first thought that they loved the cane toad.

Back in 1930,

sugar cane was the main export of

ile the toad is very adaptive, it

could not have accomplished its feats without humans!

So, let us begin our story with why

humans first thought that they loved the cane toad.

Back in 1930,

sugar cane was the main export of

important to the economy.

However,

important to the economy.

However,

Australians learned of the cane toad in 1932 when a sugar

technology conference was held in

Because sugar cane was so vital to the Australian economy, there was huge social pressure on the Australian government to “do something” about the beetle problem. With so much pressure, the government quickly decided to import the promising cane toad.

In 1935, 101 toads arrived alive in

The toads were initially released in 9 locations.

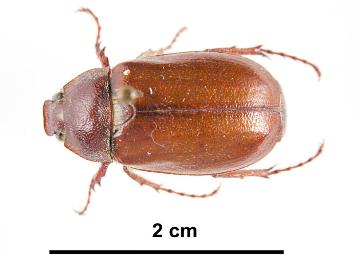

Unfortunately, the toads didn’t like Australian cane

fields. The fields were too dry and sunny for

these moisture-loving toads, and the intended food for the cane

toads were too high up in the plants for the toads to encounter

the bugs in any quantity.

All the toads might find were the

beetle larva (pictured).

Furthermore, toads are mostly

active at night, whereas beetles prefer daytime activity). The

only “thing” the toads received out of the cane fields was the

cane toad name.

Ever adaptive, however, the toads moved out of the failed

cropland habitat and into the rest of

plants for the toads to encounter

the bugs in any quantity.

All the toads might find were the

beetle larva (pictured).

Furthermore, toads are mostly

active at night, whereas beetles prefer daytime activity). The

only “thing” the toads received out of the cane fields was the

cane toad name.

Ever adaptive, however, the toads moved out of the failed

cropland habitat and into the rest of

In the wild, cane toads prefer grasslands

to dense forests, in which their big bodies and short legs make

navigation more of a challenge.

Regardless,

they found plenty of food…insects, other frogs, small rodents,

small birds, snails, small snakes, and pretty much anything else

that would fit into their mouths!

Because they have poison glands behind

their ears, few creatures could eat them and

live to brag about it…none of the creatures which might eat them (snakes, birds,

monitors, crocodiles, wild cats and dogs) had evolved to deal

with toad toxins, because they hadn't been

exposed to toads.

In the wild, cane toads prefer grasslands

to dense forests, in which their big bodies and short legs make

navigation more of a challenge.

Regardless,

they found plenty of food…insects, other frogs, small rodents,

small birds, snails, small snakes, and pretty much anything else

that would fit into their mouths!

Because they have poison glands behind

their ears, few creatures could eat them and

live to brag about it…none of the creatures which might eat them (snakes, birds,

monitors, crocodiles, wild cats and dogs) had evolved to deal

with toad toxins, because they hadn't been

exposed to toads.

Put it this way: it takes time for species to evolve the ability to survive much less easily tolerate a poison, and when a toxin (or cane toad) suddenly appears, that evolution has not had time to occur. The result is that this toxic toad has no real enemies in this non-native habitat…the few creatures that dare even attempt to eat it often die.

So, the cane toad has

plenty of food and no enemies.

Any guess what

this means?

It is the perfect storm for a

population explosion: cane toads everywhere.

They out-eat their smaller competitors, then they out-breed them

too (how can any amphibian produce more offspring than the cane

toad, when one female cane toad can lay 30,000 eggs in one

batch, and the toads grow into mature adults faster than those

of native species?).

And so, entire species

collapse --either from being eaten by the cane toad, or starved

due to the cane toad’s voracious appetite, or its eggs and

offspring outdone by the cane toad--

and eventually the altered

species populations effect the entire ecosystem.

And, the toads can spread at up to 17-31 mi (27-50 km)

each year in the most favorable of habitats.

In some locations, there are 5000 toads per acre.

They are taking over

entire species

collapse --either from being eaten by the cane toad, or starved

due to the cane toad’s voracious appetite, or its eggs and

offspring outdone by the cane toad--

and eventually the altered

species populations effect the entire ecosystem.

And, the toads can spread at up to 17-31 mi (27-50 km)

each year in the most favorable of habitats.

In some locations, there are 5000 toads per acre.

They are taking over

On to a somewhat nicer topic,

consider the cane toad in the

human environment.

Humans provide the habitats that these cane toads loved:

humans clear dense forest in favor of grasslands, parks, and

cities. Human habitats (cities) often provide

the cushy life for toads:

there’s shade,

water, and the light.

Light?

Well, the cane toads don’t care directly about the light,

but about the concentrated bug populations that swarm lights.

Its as if, instead of having to scavenge for food, the

cane toads need only appear at the dining room table – all

courtesy of humans.

There are also humans

that like the toads and thus intentionally feed them.

Cane toads are even known to eat cat and dog food, and to

learn and then appear at

the scheduled feeding times.

Cane toads must think that humans love them…providing the

easy life.

the scheduled feeding times.

Cane toads must think that humans love them…providing the

easy life.

Cane toads must think that humans love

them…providing the easy life.

Yet in reality,

there are many people that dislike them.

Some

people will intentionally swerve back and forth across a road,

trying to kill as many cane toads as possible.

This is almost a sport to people, as not only does it

reduce the numbers of what has become a nuisance species, but

the toads make a popping sound as they explode when hit.

There are also government programs aimed at reducing-and

hopefully but unrealistically eradicating-

the cane toad population.

(See

Anuran Populations for

more on population control efforts).

The

native range of cane toads

includes the huge swath of

land from

Due

to mostly intentional human transport, today cane toad exist

in over 50 countries or territorie

Due

to mostly intentional human transport, today cane toad exist

in over 50 countries or territorie s.

Humans have introduced the cane toad to the following:

Japan, Philippines, Taiwan, Thailand, Egypt, Mauritius, Bermuda,

US (Hawaii (5 islands), Florida, Louisiana), Antigua, Barbados,

Cuba, Dominican Republic, Grand Cayman, Grenada, Hispaniola,

Haiti, Jamaica, Martinique, Puerto Rico, US Virgin Islands,

British Virgin Islands, Australia, Papua New Guinea, American

Samoa, Fiji Islands, Solomon Islands.

No

doubt about it, this toad has more stamps on its passport than

due most people!

s.

Humans have introduced the cane toad to the following:

Japan, Philippines, Taiwan, Thailand, Egypt, Mauritius, Bermuda,

US (Hawaii (5 islands), Florida, Louisiana), Antigua, Barbados,

Cuba, Dominican Republic, Grand Cayman, Grenada, Hispaniola,

Haiti, Jamaica, Martinique, Puerto Rico, US Virgin Islands,

British Virgin Islands, Australia, Papua New Guinea, American

Samoa, Fiji Islands, Solomon Islands.

No

doubt about it, this toad has more stamps on its passport than

due most people!

Humans introduced cane toads to many areas in an attempt to control pests, primarily insects such as those that destroy sugar cane crops. It is from its attempted sugar cane application that its common name of “cane toad” is derived. The toad likes to live near fresh water. Their scientific name, Bufo marinus, translates to “marine toad,” but they aren’t marine (although tadpoles can tolerate brackish, or partially salty, water). They require freshwater, even when they live along coastlines.

Well, it sure looks innocent!

Now, learn what the cane toad eats!