Pathology of Clostridium difficile

How does Clostridium difficile enter

the body?

How does Clostridium difficile enter

the body?

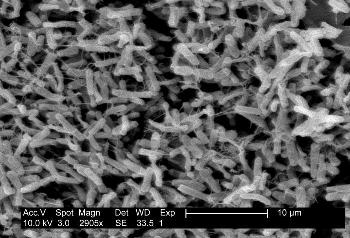

C. difficile enters a

person’s body via ingestion of the spores (for more information on spore

formation, go to General Characteristics). These spores can survive

up to two years on inanimate objects and are spread via the fecal-oral

route. The fecal-oral route most often involves someone touching a surface

contaminated C. difficile spores and then

touching their mouth with the contaminated hand. (Not surprisingly,

HANDWASHING is the best way to prevent C. difficile infections.) After ingestion, spores travel unharmed through

the acidic environment of the stomach and germinate into the vegetative

form.

vegetative

form.

From: (Public Domain) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009.

<URL:http://phil.cdc.gov/phil/home.asp>. Accessed 31 March 2009

Why does Clostridium difficile cause

disease in some people and not in others?

In an otherwise healthy person, the person’s

normal microflora of the intestines prevents C. difficile from

growing due to limited space and resources. However, when people are taking

significant amounts of antibiotics to treat another illness, the antibiotics

kill off the normal microflora of the intestines allowing C. difficile

to colonize the intestine and grow out of control. C. difficile is

most often acquired nosocomially (acquired secondary to a primary

hospitalization) because, in the hospital, patients are often on

broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy (antibiotics, such as clindamycin, used to

treat a number of bacterial infections) to prevent any infection.

Nevertheless, these antibiotics can cause pathogenic strains of C.

difficile to grow out of control. Pathogenic strains of C. difficile

can cause C. difficile- associated disease or CDAD.

CDAD affects more than 300,000 hospitalized patients yearly in the United

States.

How does Clostridium difficile cause

disease?

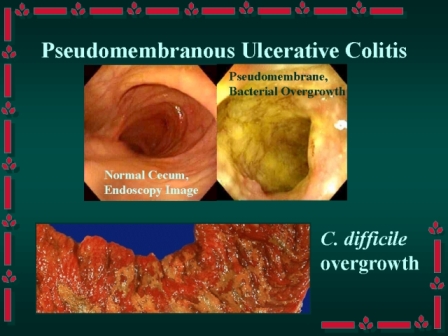

If the normal microflora of a person infected

with C. difficile has

been disrupted by antibiotic therapy, C.

difficile bacteria are able to reproduce in the intestinal crypts.

Pathogenic strains of C. difficile causes disease by the release of

two protein enterotoxins, toxin A and toxin B, which cause severe

inflammation and mucosal injury to the colon--colitis. At this point, the

toxins attract white blood cells to the area, and the white blood cells may

provide a protective immune response. However, if the white blood cells do

not provide the desired immune response, mild CDAD occurs. Nevertheless, the

toxins can actually kill the lining of the intestine, causing it to fall off

and mix with the white blood cells and give the appearance of yellow plaques

(patches) in the intestines. This is called pseudomembranous colitis because

the patches look like membranes but aren’t true membranes. (Check out

this video of a colonoscopy of a colon with pseudomembranous

colitis and note the yellow patches in the intestines.)

From: Johnson, M. T. 2009. Medical Microbiology

What are the symptoms of mild CDAD and severe

pseudomembranous colitis?

Mild CDAD * Non-bloody, watery diarrhea (5-10 watery stools

a day) * Low-grade fever *Abdominal cramping *Dehydration *Nausea *Loss of appetite

Pseudomembranous colitis (in

addition to mild symptoms) *Profuse watery diarrhea (greater than 10 watery

stools a day) *High fever (102°F—104°F) *Blood in the stool *Weight loss *Severe abdominal pain and tenderness *Death (6%-30% mortality rate) For information on treatments for CDAD and

pseudomembranous colitis, check out the

treatment page.

Who is most likely to get a Clostridium

difficile infection?

People who: *are taking more than one kind of antibiotic * have prolonged hospitalizations *are elderly *already have a disease of the intestine *are undergoing chemotherapy *have other serious diseases

Pathogenesis of Clostridium difficile-Associated Disease

Now that you have learned how C. difficile causes disease, you

should learn how the disease is

diagnosed, treated, and

prevented.

<URL:

http://web.indstate.edu/thcme/micro/anaercult/sld022.htm>.

Accessed 7 April 2009.

<URL:http://www.southend.nhs.uk/Hospital+Services/Other+Services/Infection+Control/Clostridium+Difficile/>.

Accessed 7 April 2007.