Reproduction

Bubo

virginianus are oviparous, meaning they bear their young in

the form of eggs (Walters 1994). Before the female owls lay

their eggs, they must find their mate and select a location to

nest. About two months prior to mating, the owls find their mate

(Alderfer 2005, Robbins Jr. 1994). Like most birds, the males

attract the females (Kinstler 2009). The male advertises

themselves by a variety of calls; the most common call heard to

attract a partner is a short excited hoot (Elphick et al.

2001, Kinstler 2009, Robbins Jr. 1991). To download owl calls

and hear this call,

click here. Once the female has

selected her mate, it is common for the pair to remain partners

until one dies (Elphick et al. 2001). Next, the pair

must find a site for their nest. Bubo virginanus

usually do not make their own nests; instead they will choose a

natural or manmade cavity or take over old nests. For example,

great horned owls will take over an old red-tailed hawks nest

(Elphick et al. 2001, Robbins Jr. 1994). These nests

are typically found at mid canopy where cover is offered away

from other species (Rohner et al. 2000). After mates

are selected and nests are chosen, the female may lay her eggs;

this usually occurs between January and April (Alderfer 2005).

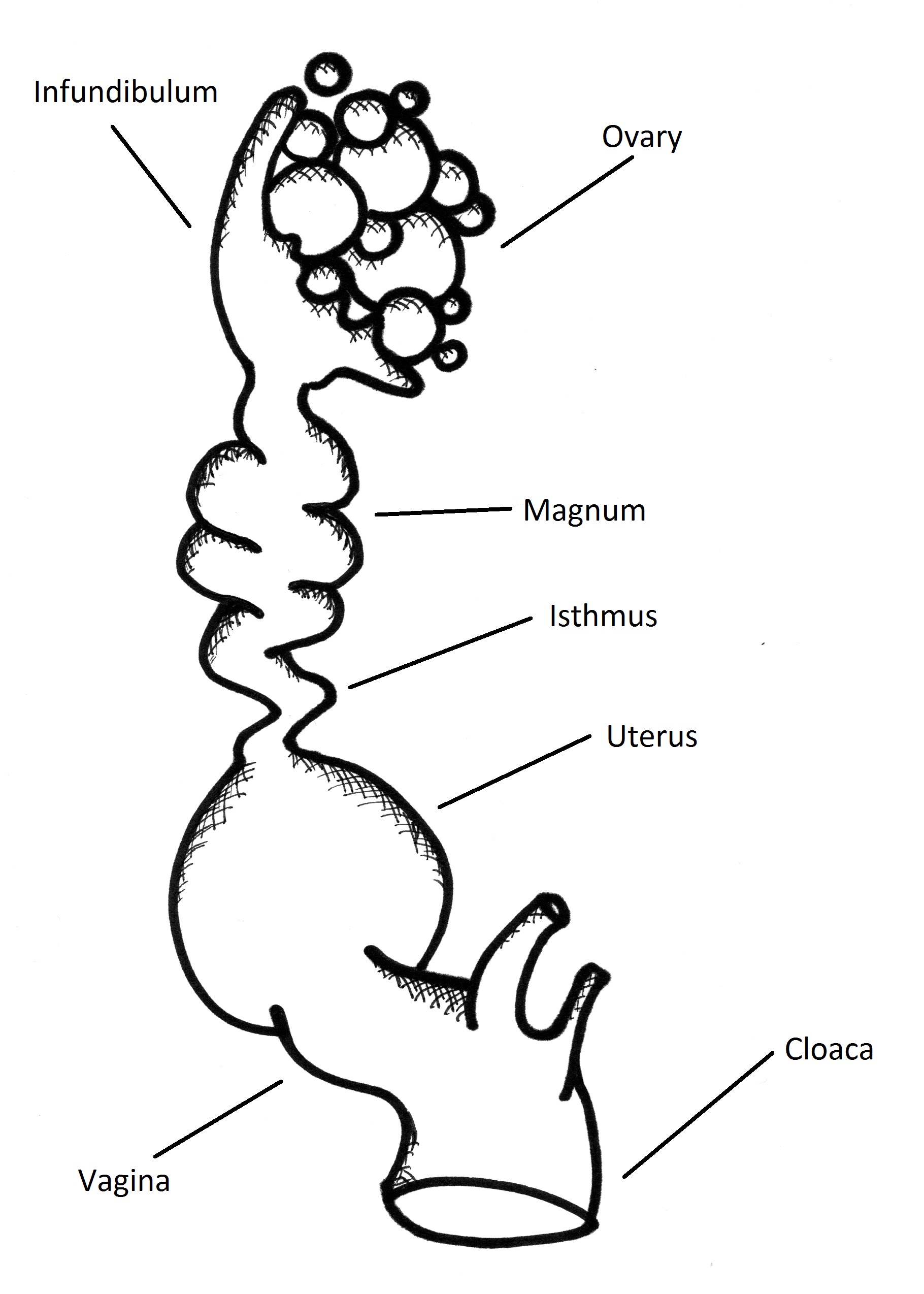

Actual reproduction of Bubo

virginianus begins within the females' reproductive system.

A male bird first fertilizes the egg; in the ovary the egg then

becomes a developing embryo. As the egg gets carried into the

magnum region, layers of yolk travel closely behind (Ritchison).

Yolk serves as a food source for the embryo; it is made of

lipids and proteins (Ritchison, Walters 1994). After an egg has

been laid, the yolk also rotates and helps keep the embryo in an

upright position (Walters 1994). After the embryo enters the

magnum, the egg is coated with a layer of albumen (Ritchison). The albumen layer is the clear part of an egg; it is made of

water and proteins that provide an extra coating of protection

(Walters 1994). Next, the egg passes through the isthmus and

gains a shell membrane (Ritchison). The egg continues in to the

uterus where the hard shell is applied making the spherical egg

shape specific to owls (Elphick et al. 2001,

Ritchison). The hard outer shell is made of calcium, which

provides protection for the embryo; it also includes an outer

cuticle providing further protection from bacteria. The outer

shell is also porous to allow for gas exchange (Walters 1994).

Lastly, the egg passes through the vagina and cloaca to be laid.

It is typical for great horned owls to lay 2-3 eggs per clutch

(Robbins Jr. 1991). For further detail on how the eggs are made

and general anatomy of birds, you can visit Professor

Ritchison's webpage

Avian Biology.

exchange (Walters 1994).

Lastly, the egg passes through the vagina and cloaca to be laid.

It is typical for great horned owls to lay 2-3 eggs per clutch

(Robbins Jr. 1991). For further detail on how the eggs are made

and general anatomy of birds, you can visit Professor

Ritchison's webpage

Avian Biology.

After an egg has been laid, it

must be incubated while it develops or it will not survive. Too

high of temperatures will kill the embryo, where low

temperatures will slow the development of the embryo and

potentially kill it. Mothers achieve keeping their young warm by

shedding feathers on their chest area and laying their exposed

skin on the eggs; this gives direct heat to the eggs (Ritchison,

Walters 1994). The female will incubate the eggs for about 35

days; the male will hunt and provide food for her during this

time (Elphick et al. 2001). After complete

development, the baby bird pecks creating cracks in the shell

until it can eventually pull itself out (Ritchison). For the

first couple weeks, the fledglings do no leave the nest; the

father hunts and provides food for the young (Elphick et al.

2001). After about three months of the fledging period, the

young owls are ready to leave the nest, but they cannot fly

until they are about ten weeks old (Alderfer 2005, Elphick

et al. 2001).

<<Adaptation Home Interactions>>