Nutrition

Yet again, because no information is

available for this species pertaining to its nutritional needs we

will focus on the nutrition of terrestrial snails, as a whole.

Diets among terrestrial snails vary

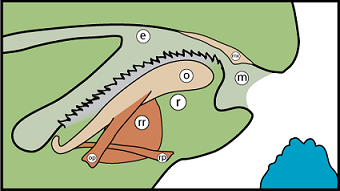

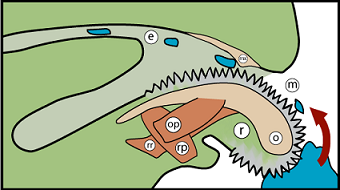

rather widely (Hotopp and Pearce 2006). They use their radula

to eat on the move, evaluating what is taken up as it slowly moves

along (Hotopp and Pearce 2006). Terrestrial snails eat

anything from rotten wood, algae, sap, herbaceous plants to animal

carcasses, and the species which are carnivorous will eat other

snails as well as nematodes (Hotopp and Pearce 2006).

Land snails spend a disproportionate

amount of time crawling around and attempting to find food (Hotopp

and Pearce 2006). There are few predatory land snail species.

Terrestrial snail species tend to be omnivorous or herbivorous (Hotopp

and Pearce 2006). Snails have a specialized tongue-like organ

called a radula used for obtaining food (Nordsieck 2011). The radula is equipped with teeth made of a material called chitin

(Hickman et al 2012), and these teeth, which feel like sandpaper,

help to scrape up food particles into the mouth (Hotopp and Pearce

2006). Once the particles are lapped up by the radula they

enter the esophagus on the way to the gastric pouch, where the

digestive gland assists in digestion and excretion (Hotopp and

Pearce 2006).

Terrestrial snails have an open

circulatory system consisting of blood vessels and sinuses and a

heart (Hickman et al 2012). Because this is an inefficient way

to disperse oxygen throughout the body, snails, like other animals

with an open circulatory system tend to be slower (Hickman et al

2012).

Some terrestrial snail species are

intermediate hosts to different parasites (Hotopp and Pearce 2006),

though our species does not seem to be one of them.

Re