Adaptation

Species belonging to the genus

Tabanus have developed

into the one of the largest genus of the “True flies.”

They are very strong fliers, which allows the females to fly

just out of reach of their vertebrate prey and the males to rapidly

fly from flower to flower feeding on nectar (Arnett

1985). One

species that is closely related to

Tabanus longiglossus (in

the same genus) can reach flight speeds of 150 km/hour (Resh

and Carde

2003)! Some

adaptations that characterize the genus Tabanus may have arose

allowing for their rapid flight.

One of these adaptations is a body that lacks bristles.

Another adaptation is their distinctively large calypteres

(lobes located at the posterior side of the wing) (Arnett

1985). We

believe that there should be some additional study done to see if

there is any correlation between their unusually large calypteres

and body that largely lacks bristles (these are unique to this

genus) that result in their increased flight speed.

Tabanus longiglossus

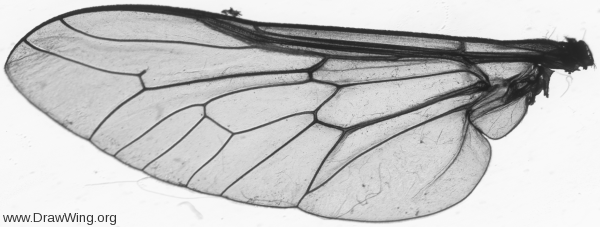

wings are similar to the rest of the flying insects given that

they are thin and membranous.

Just like the rest of the species falling under the order

Diptera, they have only one pair of primary flight wings called

patent flight wings and a reduced set of halteres, which are used

for balance in flight (Wilegmann,

2007). Their

wings are almost transparent and either colorless or smoky (Resh

and Carde

2003). This

species also has an annulated, as opposed to a segmented, antennae (Borror

and White

1970).

Another adaptation Tabanus

longiglossus has developed is their large compound eyes.

They are very large and compose almost all of their head.

They are generally green or purple earning them the name

“green heads.” To learn other

nicknames for horseflies you can go to the

interesting facts page of this website. The eyes

are separated in the females, but are united dorsally in the males (Arnett

1985). These

eyes give them an acute sense of sight allowing the females to use

visual cues to locate host that they can feed upon.

They are also, amazingly, able to sense plumes of carbon

dioxide produced during respiration of the vertebrates they seek to

feed upon (Resh

and Carde

2003).

Tabanus may have arose

allowing for their rapid flight.

One of these adaptations is a body that lacks bristles.

Another adaptation is their distinctively large calypteres

(lobes located at the posterior side of the wing) (Arnett

1985). We

believe that there should be some additional study done to see if

there is any correlation between their unusually large calypteres

and body that largely lacks bristles (these are unique to this

genus) that result in their increased flight speed.

Tabanus longiglossus

wings are similar to the rest of the flying insects given that

they are thin and membranous.

Just like the rest of the species falling under the order

Diptera, they have only one pair of primary flight wings called

patent flight wings and a reduced set of halteres, which are used

for balance in flight (Wilegmann,

2007). Their

wings are almost transparent and either colorless or smoky (Resh

and Carde

2003). This

species also has an annulated, as opposed to a segmented, antennae (Borror

and White

1970).

Another adaptation Tabanus

longiglossus has developed is their large compound eyes.

They are very large and compose almost all of their head.

They are generally green or purple earning them the name

“green heads.” To learn other

nicknames for horseflies you can go to the

interesting facts page of this website. The eyes

are separated in the females, but are united dorsally in the males (Arnett

1985). These

eyes give them an acute sense of sight allowing the females to use

visual cues to locate host that they can feed upon.

They are also, amazingly, able to sense plumes of carbon

dioxide produced during respiration of the vertebrates they seek to

feed upon (Resh

and Carde

2003).