Interactions

Devil's hair is a parasitic plant that attaches to its host's phloem and literally sucks the life out of it. Crops that are commonly affected by Cuscuta pentagona include: cranberries, alfalfa, tomatoes, potatoes, and sugar beets (Cook, 2006), but there are many angiosperms that serve as Cuscuta hosts (Freckmann, 2000). This leaves the host plant weak and more prone to disease. Other organisms Cuscuta interacts with directly include pollinators. More about this can be read in Reproduction.

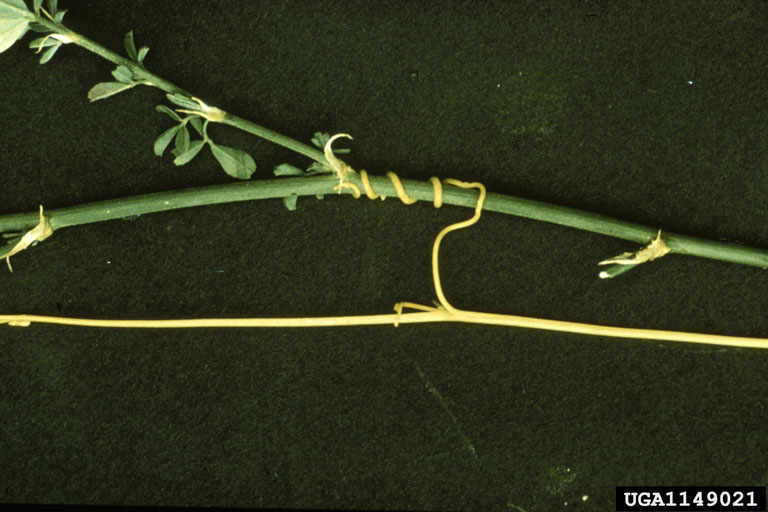

As a parasitic plant, Cuscuta is almost completely lacking in photosynthesis. Dodder doesn't need to produce its own food through photosynthesis because it is able to suck food out of a host plant. Cuscuta uses a structure called a haustorium to penetrate into its host's phloem (Cook, 2006). Once dodder taps into the host's food source-the phloem-it no longer needs to make its own food through photosynthesis. More about this can be read in Nutrition. It is thought that the stem may still be slightly photosynthetic, mostly to store up food for the seed (Revill, et al. 2005).

The roots of dodders are lacking as well (Sherman, et al. 2008). Having less root may allow for the plant to sprout in a shorter time, which gives Cuscuta more time to find a host without exhausting the food source of the seed. Dodders also have little need for roots. After sprouting, dodders detect volatile cues, which are kind of like odors given off by other plants. Cuscuta can even differentiate between plants via these smells (Runyon, et al. 2006). More about this can be read in Adaptation.

Cuscuta pentagona is one of the USDA's top ten most noxious weeds (USDA, NRCS, 2012). In cranberry beds in Massachusetts and Wisconsin, 80-100% crop loss was reported due to Cuscuta. About 30,000 acres of tomatoes are infected with Cuscuta in California. That could result in almost 75% crop loss. Cuscuta can also carry viruses and fungal infection across crops as it twines from plant to plant. (Cook, 2006)

Cuscuta is obviously harmful to crops, but controlling the spread is no easy task, as it is difficult to get rid of dodder without affecting its host (Runyon, et al. 2006). Other characteristics that make dodder more difficult to remove are its size, quick dispersal, and its long lasting, tough seed.

Many different chemicals and biological agents have been tested as herbicides to stop the spread of dodder, and a mix of biological and chemical control agents was found to be the most effective in experiments. The chemical herbicides glyphosphate and ammonium sulfate mixed with Alternaria destruens, a biological control, is the best concoction to control dodder without affecting the host plant (Cook, 2006). More about this can be read in a paper by Jennifer Cook: Integrated Control of Dodder. You can find more about this source in References.

Another way Cuscuta pentagona might be controlled is to figure out which volatile cues- chemical signals given off by plants- that Cuscuta doesn't like. There are certain chemicals that repels dodder. For example, one certain compound in wheat repels Cuscuta pentagona (Runyon, et al. 2006). This explains why certain hosts are more attractive to dodder. More importantly, if this compound could be manufactured, it could be used on crops to keep Cuscuta pentagona from harming the good plants. Another way this information could be used is to plant dodder-attractive hosts to keep Cuscuta pentagona off of the crops. This way, the host and Cuscuta could be poisoned with no harm to the crop.

Some simpler methods that have been used to slow Cuscuta pentagona are crop rotation with grains, which repel dodder, tilling to bury the seedlings, and keeping a dense canopy throughout the crop, which will hinder Cuscuta's germination. Removal by hand or machine is often fruitless work though. (Cook, 2006)

If you find dodder in your own garden, it would be best to get rid of the pest as soon as possible. Removing Cuscuta carefully from your plant would be the most economical method of control. Common herbicides would kill dodder but also would likely kill the host plant (Ombrello). It is important to catch dodder early on. Once it seeds, Cuscuta can return for many years due to its tough, long lasting seed. For more about the seed of Cuscuta pentagona, go to Adaptation and Reproduction.

For a more chilling tale about the interactions

of Cuscuta pentagona, go to

Spooky Story.

Click here to go

Home.