Nutrition

Unlike most plants, Cuscuta pentagona isn't autotrophic. It doesn't have leaves where photosynthesis could take place or roots where nutrients could be absorbed. Over time, Cuscuta has lost most of its ability to photosynthesize. The stem of dodder is thought have retained some of this ability. (Revill, et al. 2005)

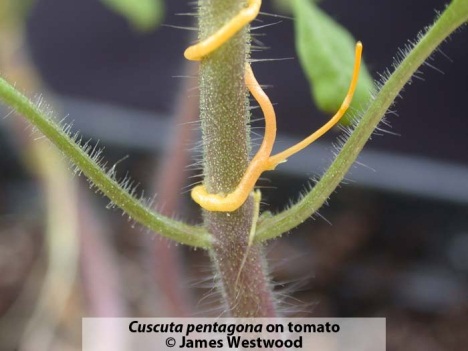

As a parasitic plant, dodder relies on a host for its food. Cuscuta pentagona feeds on various angiosperms, (Freckmann, 2000), but it is better known for destroying crops like tomatoes, cranberries, and alfalfa. Dodder is adapted to finding a good host, as well as attaching to that host. Once Cuscuta begins germination, little of the energy saved in the endosperm of the seed is used for growing roots. Minute roots are formed, and instead Cuscuta pentagona puts up a shoot almost immediately, using energy from the seed until it finds a host (Sherman, et al. 2008).

Cuscuta pentagona sniffs out a host using a sort of sense of smell (Runyon, et al. 2006). Once a host is found, Cuscuta wraps around the stem. Cuscuta uses a special structure called a haustorium to tap into its host's phloem-the plant's nutrient transport system. The haustorium is very small in order to tap into the phloem without disrupting the host's systems. Fiber-like structures grow from the haustorium to gain access to more nutrients inside the phloem (Cook, 2006). Another organism that uses a haustorium is mistletoe. More about Cuscuta pentagona's sense of smell and parasitism can be found in Spooky Story and Adaptations.

Nutrients found in the phloem are made by photosynthesis. Photosynthesis takes place mainly in the leaves of plants, then the nutrients are sent down the stem to other parts of the plant via vascular tissue called phloem. When the haustorium taps into the phloem, it siphons out nutrients that would otherwise be used in the host plant.

Click here to go to Reproduction.

Click here to go Home.