Creator of Penicillin "The Wonder Drug" *Contact |

|

| Home | General Information | Reproduction | Relationships | Penicillin "The Wonder Drug" |

|

General Information As P.

chrysogenum belongs to the most mysterious, unfamiliar kingdom

(the fungi), it is not surprising that little is commonly known

about the organism.

Thus, I have included in my webpage some general information

which may come in use some day. For

example, you may find yourself standing face to face with Alex

Trebek, a mixture of sweat and adrenaline taking over your body, and

he asks a question on the common habitat of Penicillium

chrysogenum. The

choice is yours: read on and win your wager or stop now and let the

overly intelligent, socially lacking boy who’s half your age win the

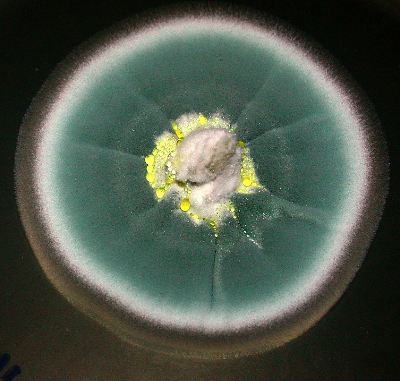

game. Structure: Like most members of the Penicillium genus, P. chrysogenum is a filamentous fungus. It usually sports a wooly to cotton-like appearance which starts out as a whitish color and over time changes to different shades of blue/green, yellow, pink or grey.Habitat/Adaptation: Because P. chrysogenum is a heterotrophic

organism, it does not depend on light to survive.

This characteristic allows the organism to live in multiple

habitats. Thus, P. chrysogenum is less likely to adapt to its

environment, but instead flourish in an environment which is adapted

to it.

Nutrition: Do you ever wonder what happens to your banana

peel when you throw it out the car window?

Or, why a forest floor isn’t forever covered in leaves after

the fall season?

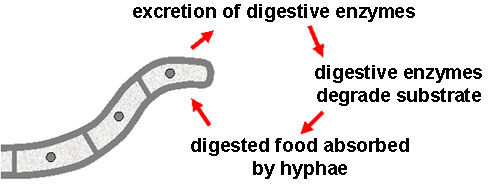

Using

digestive enzymes (called exoenzymes) fungi can break down almost

all man made and naturally occurring materials, P. chrysogenum

is no exception. The process which fungi break down complex

nutrients into more simple carbon compounds is extremely

interesting. It is a

process of first externally digesting nutrients followed by the

ingestion of them.

After P. chrysogenum ingests the nutrients, the nutrients are

spread throughout the vegetative body called the hyphae.

Any unused nutrients are stored unused as glycogen.

This is similar to the way animals store their foods. You can

learn more about this process and the different symbiotic

relationships of fungi

here.

|

|