Habitat & Geography

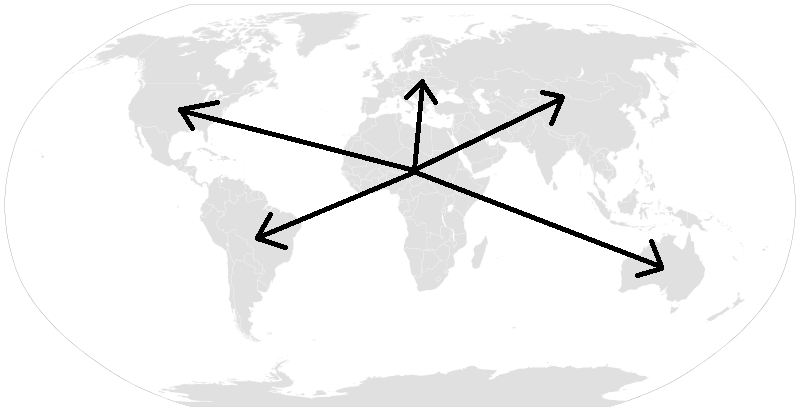

Gastrophilis intestinalis was believed to have originated

from the Old World, mainly Africa (Mullen and Durden, 2002).

They have since moved with humans and their hosts and are now

found all over the earth. They are usually seen near the

pastures of equines, such as

horses,

donkeys, and mules (Cogley

and Cogley, 1999). Their peak behavioral action is during warm

and sunny weather during the daytime (Evans et al., 2004). Even

though they spend a lot of time in the outside environment, the

main habitat of G. intestinalis is the horse itself.

During the first stage of the larva's life, it spends about three weeks in the mouth tissue and gums of the horse (McLendon and Kaufman, 2007). The very presence of moisture allows the eggs to hatch and the larvae to crawl inside its body. The function of a mammalian mouth, let alone a horse’s mouth, is to ingest food and start the breakdown of material with its saliva. Under normal conditions, the pH of saliva has a range of 6.2 and 6.8 (Aframinan, 2006). The larvae have to develop an exoskeleton before the slight acidity of saliva break down their vulnerable epidermal tissue. The normal body temperature of an equine ranges from 37-40० C (Hinchcliff, 2008). After they’re done living in the mouth, they migrate to the stomach to do the bulk of their growing (McLendon and Kaufman, 2007). Their migration from the mouth to the stomach yields the most immunological response from the horses system (Roelfstra et al., 2009). However, this immunological response isn’t nearly enough to fight off the parasitic invasion (Sandland, Personal Communication).

The larvae spend the majority of their lifetime in the stomach and intestine, a total of about 9 months (McLendon and Kaufman, 2007). Once they move to the stomach, the second instar larvae usually hook themselves on the junction on the esophageal and the cardiac regions (McLendon and Kaufman, 2007). This is the portion of the stomach where the esophagus ends and opens up to the stomach. During the period of infestation, G. intestinalis may not be the only parasite that feed on equines. There have been numerous amounts of other parasites from the Helmithes Phyla, about 13 – 18 organisms for each species (Güiris et al, 2010). The stomach is where the larvae have the most problems living. First of all, they have to try to stay secure on the stomach tissue. With horses grazing the fields up to 18 hours of the day (WorldHorseWelfare, 2012), they have to withstand the constant contractions of the esophagus conducting peristalsis into the stomach. They have adapted for this problem by having a hooked like mouthpiece and spines that point toward the posterior end of the larvae (McLendon and Kaufman, 2007). These adaptations help keep the larvae in place during the movements of the esophagus and stomach during digestion.

The bot Larvae also have to resist the high acidity of the gastric acid in the stomach. Gastric acid has a pH range of about 1 -3. That’s acidic enough to eat the stomach itself, let alone a few bugs. The larvae have an exoskeleton by this time of their lives, which is made of chitin. This chitin in the exoskeleton is capable of withstanding such high pH levels. There is an enzyme called chitinase; which does have the capability of breaking down chitin. Mammals have this enzyme, but at extremely low concentrations in their gastric acid. It is unknown whether or not mammals, insluding horses, are able to digest chitin with such low levels.(Reid, 2009). After they have fully grown in the stomach, they detach and exit out of the horse through its feces (McLendon and Kaufman, 2007).

The larvae then enter a pupation period in or near the place of excretion (McLendon and Kaufman, 2007). They are incapable of moving; as their bodies act as a cocoon. This period usually happens in late spring, early summer.

Isn't that interesting! Let's see how the horse bot fly's morphology helps it survive!

Want to go home?