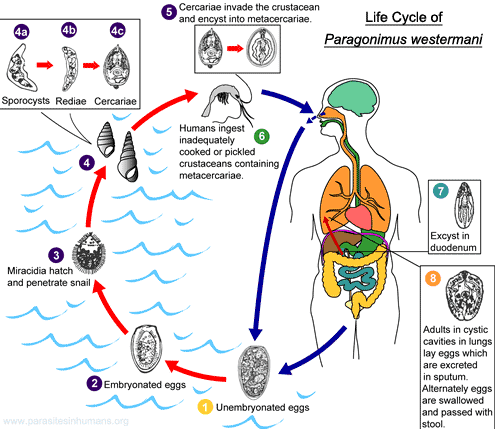

Lifecycle and Reproduction

From the egg...

Although Paragonimus westermani is a parasite pretty

much its whole life, that is not to say that it is a parasite to

one host. Rather it makes its home in three different organisms,

and which one it inhabits simply depends on which stage of its

life it is in. Starting out as an egg, after at least two weeks

this fluke hatches as a free-living and ciliated miracidium, or

larva (Liu et al. 2008). The larva will immediately start

looking for its first intermediate host, a freshwater snail.

Upon the discovery of one, the miracidium will embed itself in

the tissues of the snail and shed its cilia while maturing into

a sporocyst. At this next stage in its life, the fluke will

asexually produce two generations of cylindrical larva called

redia, the second of these which will asexually reproduce

cercariae. The cercariae are disk-shaped larva with tail-like

appendages that, from egg until now, have taken about four

months to develop (Fuller 2012).

...to the 1st..2nd...3rd..hosts

From this first intermediate (snail) host, the P. westermani

will inhabit its second intermediate host - a crab, crayfish, or

other freshwater crustacean. It does this either by being ingested

by the crustacean while still in the snail and then transferring to

the body of the new host, or by first swimming out of the snail and

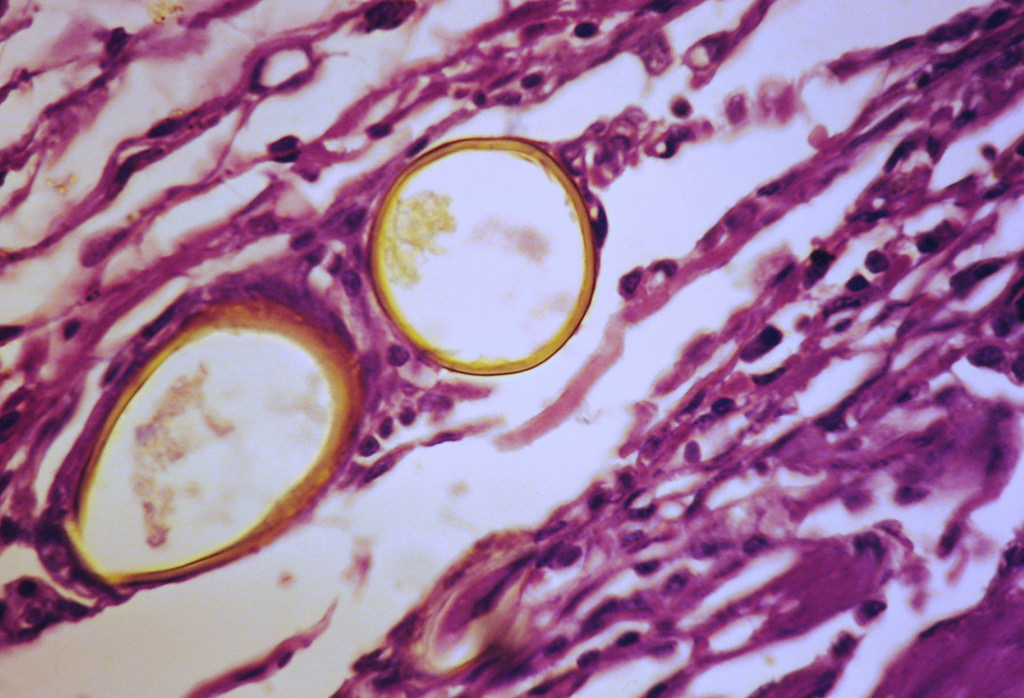

penetrating the skin of the crustacean. At this point, the cercariae

transform into metacercariae, as they become enclosed in a

thick-membraned cyst (Liu et al. 2008). Humans or other mammals, the

final hosts, then get infected by this parasite when they ingest the

raw or undercooked crustaceans populated with metacercariae. Once

inside this definitive host, the fluke will maneuver its way to the

animal’s lungs or other tissues, ultimately causing paragonimiasis

in this organism (Chen et al. 2010). However, not all mammals (such

as mice) or tissues (such as the heart) are favorable to the fluke

and therefore disallow Paragonimus westermani to develop

into an adult worm. If this is the case, and it remains in the

metacercariae stage, eggs will not be produced, the lifecycle will

not be complete, and the mammalian host will not be infected

(Shibahara 1993 and Liu et al. 2008). Just the opposite, if and/or

when the fluke does fully mature, it carries out its final duty of

sexually reproducing eggs. These eggs will then leave the mammal’s

body and be distributed out into the environment by way of saliva or

feces, and the cycle will repeat (Fuller 2012).

Forms of reproduction

When it comes to reproduction, then, this fluke will reproduce

either sexually or asexually depending on which stage of its life it

is in. As aforementioned, when maturing from the sporocyst to the

redia and the redia to the metacercariae, the parasite reproduces

asexually. In contrast, when producing and fertilizing eggs as adult

worms, sexual reproduction takes place. Hermaphroditic in nature,

sexual reproduction typically requires the worms to find a mate,

form a cyst, and exchange sperm to produce the eggs. Discoveries of

cysts containing a single worm, however, suggest that

self-fertilization is also an option for this parasite. Because of

the number of asexually produced offspring (redia and metacercariae)

within this lifecycle, Paragonimus westermani does not

invest in its young. Sheer numbers are expected to ensure the

survival of the species (Fuller 2012).

Sexual reproduction will also only take place if the fluke is diploid. Discoveries have shown that this is not always the case, though, but rather that triploid and even polyploidy P. westermani exist. Because chromosome-crossing would get complicated in sexual reproduction between flukes with excess chromosomes, those that do exceed the diploid number usually do not reproduce in this way. Instead, they engage in asexual reproduction, self-fertilization, or, as is usually the case with triploid individuals, they are parthenogenic (Park et al. 2003).

Continue to: Interactions

Return to: Home page

References