Reproduction

The Viral Hemorrhagic Septicemia virus is just what is sounds

like: a virus. Viruses, technically, are not living. Viruses are

drifting pieces of genetic material, namely DNA or RNA, that are

encapsulated within a protein coat. The do not eat, transpire,

or carry out any other metabolic processes attributed to life.

Even reproduction is not a task that a virus can accomplish on

its own, which is why it requires a host. For VHS, the hosts in

this parasitic relationship are the fish.

Infection of the host begins with contact with the virus. Fish

can be exposed to, and contract the virus in a number of

different ways. Exposure to feces, urine, or other fluids from

infected fish (such as milt) can transfer the virus. The virus

can enter into the fish via an open wound or through the gills

(though rare), and transfer of the virus also occurs when a fish

eats an infected fish. Contaminated eggs can also spread the

disease, and bait fish brought in from infected waters can as

well. This is a main reason for why local governments are trying

to get out the word on VHS, and educate fishermen and other

marine life workers.

After reaching the fish, the Rhabdovirus (contains

negative-sense, single-stranded RNA) then proceeds to infect

cells of major organs. The virus uses it’s RNA to force the cell

into making more of the virus. When the cell has made enough of

the virus, the virus bursts out of the cell, which leads to

necrosis (cell death).

After reaching the fish, the Rhabdovirus (contains

negative-sense, single-stranded RNA) then proceeds to infect

cells of major organs. The virus uses it’s RNA to force the cell

into making more of the virus. When the cell has made enough of

the virus, the virus bursts out of the cell, which leads to

necrosis (cell death).

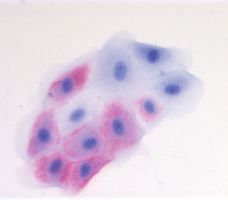

VHS (red) invading Gill Epithelium

This widespread necrosis has very damaging effects on the fish, including hemorrhaging of organs or muscle tissue, and swelling of organs or tissue. Sometimes the effects of the virus can be seen externally on the fish as well, such as red spots seen on the surface of the fish.

Back to Prevention Home On to Interactions