Interactions

Since Bithynia tentaculata is nonindigenous to the North American

ecosystems, its interactions with other organisms are often

detrimental to the native organisms.

For example: (Kipp and Benson 2010)

- In the Erie Canal the faucet snail is replacing two pleurocerid snails species, Elimia virginica and E. livescens.

- In Lake Champlain it dominates the gastropod population.

- In Oneida Lake, mollusk diversity has decreased by 15%. The invasive zebra mussels, Dreissena polymorpha has since decreased the number of B. tentaculata but has decreased the mollusk diversity even further.

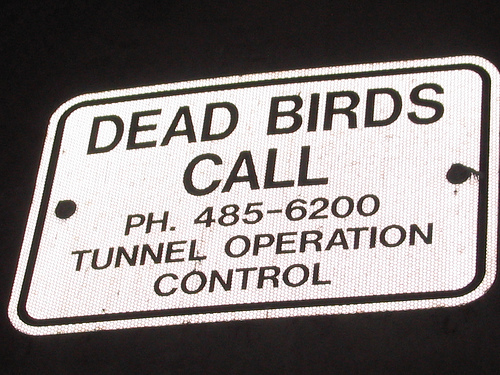

Another important interaction is between

B. tentaculata and the

waterbirds of the Upper Mississippi River(UMR), specifically Lake

Onalaska. During the 2006 spring migration, an estimated

22,000-26,000 birds died on the Upper Mississippi River National

Wildlife and Fish Refuge (Sauer, et al. 2007). The majority of the

bird deaths were

lesser scaup, and

American coots, but others were also affected such as the

northern pintail, American wigeon, northern shoveler,

blue winged teal,

mallard, American black duck, gadwall, redhead, ring-necked

duck,

bufflehead, tundra swan, hering gull, and the ruddy duck (Sauer,

et al. 2007). Cause of death was found to be from infection by two

trematode parasites,

Cyanthocotyle bushiensis and

Sphaeridiotrema globulus (Sauer, et al. 2007). And sure enough,

our friend the faucet snail is the vector passing trematode

infection to the waterbirds that eat this snail. B. tentaculata is the first

and second intermediate host in the trematode life cycle (Sauer, et

al. 2007).

For more information about these

trematodes and other parasitic diseases follow this link.

Trematode Life Cycle: (Cole and Friend 1999)

- Trematode eggs are released into the water through the feces of infected birds.

- These eggs become free-swimming and infect the primary intermediate host, Bithynia tentaculata and continue to develop.

- After some development, the parasite is called cercariae and is released from B. tentaculata.

- This free-swimming cercariae becomes encysted on

as metacercariae on or in the second

intermediate host, which is also B. tentaculata. - When waterbirds consume these snails, they

become infected and the trematode life cycle

continues.

Infection by this parasite is not beneficial to B. tentaculata because it is capable of castrating the snail, therefore reducing the reproduction potential of the population (Wächtler 2001). The egg laying, female faucet snails are also more likely to be infected; however the majority of infected females are still able to lay eggs (Wächtler 2001). Despite the fact that the faucet snail may be castrated, the waterbirds suffer most from this parasite infection. The trematode, Sphaeridiotrema globulus, causes infected birds to be lethargic, have bloodstained vents and have lesions and inflammation in their small intestine (Cole and Friend 1999). S. globulus feeds on blood, resulting in severe blood loss and the bird most often dies from hypovolemic shock (Cole and Friend 1999). Cyanthocotyle bushiensis is found in the lower intestine and cecae of infected waterbirds where it causes hemorrhage and plaque formation eventually blocking the intestines and weight loss (Cole and Friend 1999). The bird most often dies from vascular leakage causing dehydration (Cole and Friend 1999). This parasitic infection is so detrimental to these waterbirds because only a small number of trematodes is needed to cause death.

Return to the

Home page