|

| |

|

Mycobacterium

tuberculosis |

|

Pathogenesis |

|

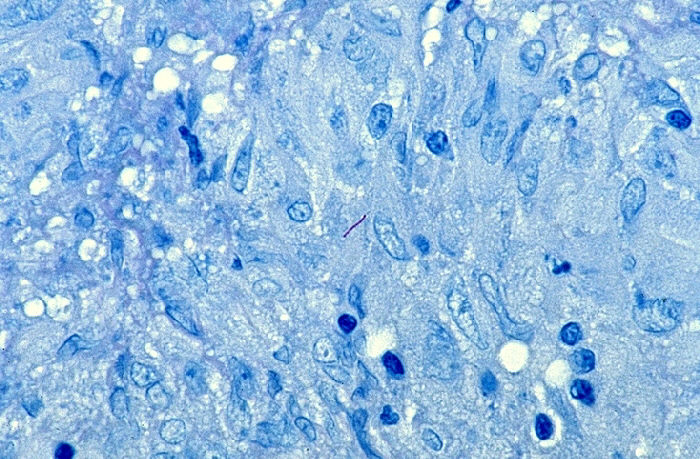

Infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis

begins when droplet nuclei are inhaled into the upper respiratory tract

through the mouth or the nose (Figure 2, box 1). From the upper respiratory tract, the

bacilli travel through the bronchi until they reach the alveoli of the

lungs (Figure 2, box 2). Once inside the lungs, alveolar macrophages (immune cells that

engulf foreign particles) ingest the pathogenic organisms, but the mycobacteria do not die. Instead, the bacilli multiply within the

macrophage hosts, causing the macrophages to rupture. The continued

division of M. tuberculosis every 18 to 24 hours attracts more

and more immune cells to the area. In an attempt to control the

infection, some of these cells produce toxic substances that are

supposed to kill the bacilli. The bacilli do not immediately die,

however, so the release of toxic substances also damages the surrounding

lung tissue. When macrophages and other cells of the immune system

encircle this area of dead tissue, the lesion is called a tubercle or

granuloma (Figure 1).

|

|

|

Figure 1. Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli visible

within granuloma. This tissue sample was taken from the

endometrial layer of the uterus. This is an example of

tuberculosis disease persisting in an area of the body outside of the

lungs.

|

The interior of a tubercle consists of a gelatinous mass of host cells

and bacilli that gives the damaged tissue a cheese-like consistency.

Therefore, this type of tissue death is referred to as caseation necrosis. If the

immune system is successful in preventing the M. tuberculosis

bacilli from multiplying further, the caseous tubercles become

walled-off and calcified (Figure 2, box 4). Although calcified lesions still contain

viable bacteria, the bacteria cannot be spread to other individuals.

When Mycobacterium tuberculosis lies dormant in the lungs, a

person is said to have a latent tuberculosis infection. Such persons,

who represent 85-95% of infected individuals, show no overt symptoms of

disease.

|

In

5-15% of infected individuals, the immune system fails to prevent the

infection from progressing and the interiors of the caseous lesions become liquefied.

Liquefaction allows viable M. tuberculosis bacilli to spill out

of the tubercles, leaving behind a cavity in the lungs (Figure 2, box 5). When these

bacilli infect lower portions of the lungs or enter the bronchi the

result is an active case of pulmonary tuberculosis disease. People with

pulmonary tuberculosis are capable of spreading the disease to others

through the bacteria in their sputum. They also manifest symptoms such

as weight loss, weakness, night sweats, chest pain, and coughing up

blood. If viable bacilli enter the bloodstream, M. tuberculosis

can travel to organs of the body outside of the lungs (Figure 1, above

and Figure 2, box 3). Known as

extra-pulmonary tuberculosis, this form of the disease is rarely

contagious.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As mentioned earlier,

people with latent tuberculosis infection retain viable M.

tuberculosis bacilli within their lungs, even though they are

asymptomatic and not infectious. When a person with latent TB becomes

immunosuppressed because of old age, lifestyle choices, illness, or a

medical condition such as HIV, the dormant bacteria can reactivate

within the calcified tubercles. Thus, people with latent tuberculosis

infection always run the risk of developing active TB disease. |

|