Interactions

Horrif-EYE-ing symptoms!

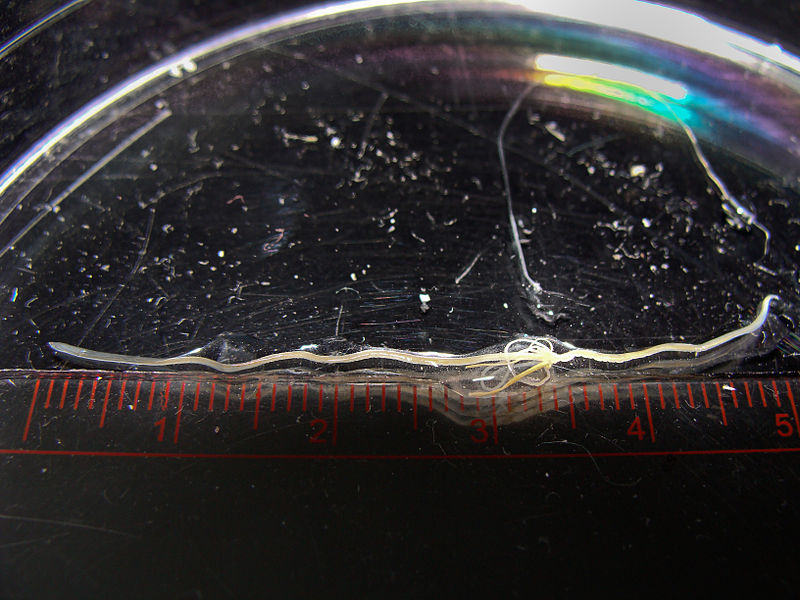

The Loa loa is without a doubt a parasite in that the parasite

benefits while the host is harmed during the relationship; the

Loa loa benefits by feeding on bodily fluids underneath

the skin (Padgett and Jacobsen 2008). These parasites differ

from other thread-like

nematode parasites; they have nuclei

throughout their entire body while similar parasites do not have

their nuclei extend as far (Padgett and Jacobsen 2008). Learn

more about their morphology

and how it increases reproductive

success. A human infected with this parasite can experience

everything from no symptoms at all to spreading a disease called

filariasis, which can cause Calabar swelling (Padgett and

Jacobsen 2008). This swelling appears on the limbs and joints,

making the skin very irritated and movement painful (Padgett and

Jacobsen 2008). Another negative effect these parasites can

cause is extreme pain when migrating throughout the body tissues

(Padgett and Jacobsen 2008). This parasite rarely affects one’s

vision, however the inflammation as a result from the migration

of the parasite can cause temporary blindness that can endure

anywhere from a few minutes to a few hours (Padgett and Jacobsen

2008). Along with that, the Loa loa can mature in 1-4

years and can remain alive in your body for as long as 17 years!

(Padgett and Jacobsen 2008).

can experience

everything from no symptoms at all to spreading a disease called

filariasis, which can cause Calabar swelling (Padgett and

Jacobsen 2008). This swelling appears on the limbs and joints,

making the skin very irritated and movement painful (Padgett and

Jacobsen 2008). Another negative effect these parasites can

cause is extreme pain when migrating throughout the body tissues

(Padgett and Jacobsen 2008). This parasite rarely affects one’s

vision, however the inflammation as a result from the migration

of the parasite can cause temporary blindness that can endure

anywhere from a few minutes to a few hours (Padgett and Jacobsen

2008). Along with that, the Loa loa can mature in 1-4

years and can remain alive in your body for as long as 17 years!

(Padgett and Jacobsen 2008).

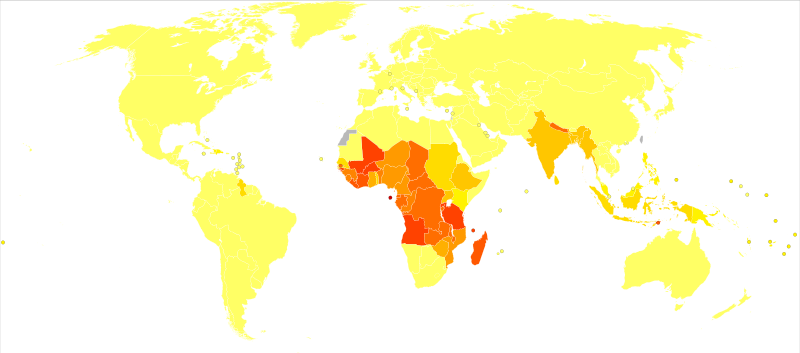

This could directly affect YOU!

How are these eye-soar suckers

spread?

The

life cycle of this nematode reveals just how they are

transmitted to humans- from the help of three different species

of Chrysops fly: Chrysops dimidiata, Chrysops

silacea, and

Chrysops langi (Padgett and Jacobsen

2008). Research does not indicate weather the larva of Loa

loa brings them any harm; they act more as a vessel to the

true destination: the human host. They generally inhabit

swampy areas with a body of water and a plentiful source of

decaying plant material (Padgett and Jacobsen 2008). Females

require a wet environment to lay their eggs as well as a blood

supply for energy and reproduction. These flies find their way

to humans because they are attracted to smoke from wood fire as

well as carbon dioxide we exhale (Padgett and Jacobsen 2008). It

all starts with a bite from one of these flies who carry the

developing larva of the Loa loa (Padgett and Jacobsen

2008). The bites from these flies differ from a puncture from a

mosquito; these flies create a slit then lap up the blood from

the host, which creates a pathway for the parasite to

enter (Padgett and Jacobsen 2008). When the larva enters the

human body, they must first be capable of crawling from the

mouth of the

fly into the bite (Padgett and Jacobsen 2008). They

mature under the skin of humans into the adult stages where the

fly will bite again and ingest the larva to carry it to another

human host (Padgett and Jacobsen 2008). From there, all it takes

is 12 days after exposure for these parasites to start to

develop (Antinori et al. 2012).

How do you get rid of these pests?

The most common methods of treating these parasites are surgical

extraction and antimicrobial drugs(Pagett and Jacobsen 2008).

The only problem with extraction is that it is tough to kill off

all traces of the parasite while the drugs are more effective in

that way (Pagett and Jacobsen 2008). However, some of the drugs

have negative side effects; in some cases when diethycarbamazine goes

through the blood stream, it causes brain swelling or

retinal seepage (Pagett and Jacobsen 2008). Ivermectin is the

most effective way to treat this infection yet it also has some

serious side effects: coma inducing, brain swelling, retinal

seepage, and kidney damage (Pagett and Jacobsen 2008). Research

suggest that there is a direct relationship between the

increased risk of

having a deadly reaction to ivermectin and the severity of the

infection or “population” of Loa loa (Gardon et al.

1997).

drugs are more effective in

that way (Pagett and Jacobsen 2008). However, some of the drugs

have negative side effects; in some cases when diethycarbamazine goes

through the blood stream, it causes brain swelling or

retinal seepage (Pagett and Jacobsen 2008). Ivermectin is the

most effective way to treat this infection yet it also has some

serious side effects: coma inducing, brain swelling, retinal

seepage, and kidney damage (Pagett and Jacobsen 2008). Research

suggest that there is a direct relationship between the

increased risk of

having a deadly reaction to ivermectin and the severity of the

infection or “population” of Loa loa (Gardon et al.

1997).

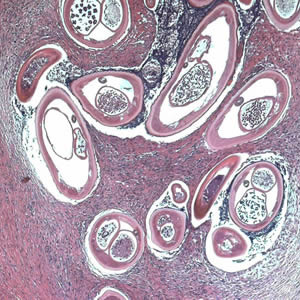

Parasite competition? Double trouble!

Onchocerca volvulus and Loa loa spell double the

trouble since they are prevalent in the same habitat and both cause human

filariases (Pagett and Jacobsen 2008). Additionally, treatment

through ivermectin therapy for patients who are infected with

both

Onchocerca volvulus and Loa loa is more risky because of the

neurological complications that can ensue from these treatments

(Pagett and Jacobsen 2008). The severe reactions to ivermectin are

not well understood; they may have to do with the rapid

effectiveness of the drugs killing the numerous larval parasites

(Pagett and Jacobsen 2008).

same habitat and both cause human

filariases (Pagett and Jacobsen 2008). Additionally, treatment

through ivermectin therapy for patients who are infected with

both

Onchocerca volvulus and Loa loa is more risky because of the

neurological complications that can ensue from these treatments

(Pagett and Jacobsen 2008). The severe reactions to ivermectin are

not well understood; they may have to do with the rapid

effectiveness of the drugs killing the numerous larval parasites

(Pagett and Jacobsen 2008).